In 1963, when Niede Guidon was a young archaeologist working at the Museu Palista in Sao Paulo, Brazil, a friend showed her some photographs of ancient paintings on rock walls. Something about those photos made a profound impression on her. The site was called Pedra Furada, Pierced Rock, after a famous rock formation with a hole in it.

The remote area of northeastern Brazil where the photos were taken, stripped of its forests in colonial times, had suffered terrible erosion, silting of rivers, and subsequent desertification by the time Guidon visited in 1973. But its isolation had helped to preserve the paintings. As soon as she began studying the area, she realized it was something extraordinary.

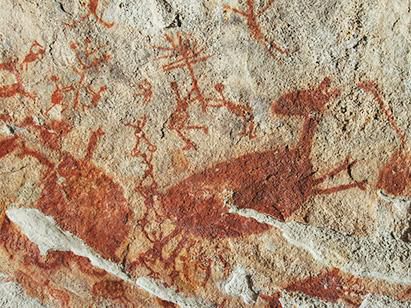

Where most rock art sites in Europe are a single cave or a series of caves in a single mountain, Pedra Furada is a collection of over 900 sites with over 1150 images painted on the walls and ceilings, mostly with red ochre or other clays, and some burned bone charcoal. The oldest images date from 12,000 years old, the newest about 5,000 years old, showing a change in style over time from fingerwork to paintings created with cactus spines and brushes made of fibers or fur. They show people hunting with atlatls (dart throwers), dancing, mating, giving birth, and fighting. Many animal are represented, including caimans, llamas, pumas, deer, capybaras, turtles, fish, and iguanas.

Often the red deer are large, surrounded by small images of people, as in the panel shown. Other sections feature rows of marks and unidentified figures, and what seem to be narrative sequences.

Some large rectangular humanoid figures with patterned bodies are surrounded by smaller human forms with raised arms.

The treasure underfoot

What lay deep in the ground near the painted walls was even more surprising than the paintings. Guidon and her team spent years carefully excavating the areas, finding evidence of hearth fires and stone tools in layers ranging from 5,000 years old to 32,000 years old, with lower levels dating to 48,000 years old. Repeated analysis by independent labs, mostly in France, supported those dates. Guidon herself, never one to shy away from an argument, maintained in a 1985 article in Nature that the site showed clear evidence of human occupation 60,000 years ago!

“Clovis First”

Her findings enraged American archaeologists because they challenged the common belief that people arrived in the Americas by walking across the land bridge from Asia, called Beringia, to Alaska during the Ice Age, about 13,000 years ago. From there, they supposedly dispersed all through the Americas.

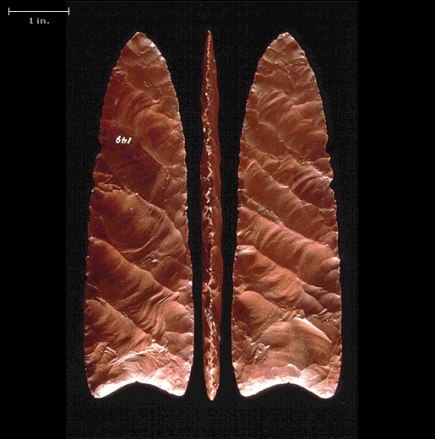

This theory began in the 1930’s with the discovery of a finely-made spear point lodged in a mastodon bone near Clovis, New Mexico. When other points/arrowheads with this same design were found in neighboring states, and then across the country, archaeologists decided that these points were made by East Asian big game hunters who followed their prey across Beringia and down an ice-free corridor between glaciers into what is now the western United States. The presence of the Clovis points became the basis for a belief in a Clovis people and a Clovis culture that was so effective it spread from north to south throughout the Americas. The Clovis First theory was repeated endlessly in school textbooks throughout the 20th century. (The Clovis point in the photo shows the characteristic fine work on both sides (bi-face).

There were a few glitches in the theory, but they were largely ignored. For instance, the greatest concentration of Clovis-style points has been found in the southeastern US, not in Alaska or northern Canada, so we can assume they moved from the east to the west, not the other way around. (See diagram of Clovis point distribution)

Plus, there was never any proof that the Clovis-style points indicated either a people or a culture. Today, iPhones are found all over the world, but they represent neither a people nor a culture. They’re simply a very useful bit of technology. Probably Clovis points were too. A valuable trade item, endlessly copied – spreading across the continent.

But all of these problems with “Clovis First” were dismissed by the established powerhouses in American archaeology, especially at Harvard and Yale.

Dennis Stanford, now with the Smithsonian Museum of History, admitted that when he was excavating a site in Florida and came across signs of human habitation far older than Clovis dates, he told his team to fill the pit back in and tell no one about it since their findings would never be accepted.

Who’s she?

Then along came this brash Brazilian woman with her French education and her crazy theories about early man in Brazil. The US archaeological community tore her findings apart, claiming the tools were made by monkeys, or they were “geofacts,” natural objects altered by weather or falling to the ground. In a heated response to a question about them from a reporter from The Guardian, Guidon said, “US archaeologists believe that the artifacts are geofacts created naturally because the North Americans CANNOT BELIEVE they do not have the oldest site!” When critics said the carbon hearth samples were the result of natural fires, she pointed out the sites lay well inside caves or rock overhangs, inside circles of stones. No carbon was found in sample pits dug outside the shelters. “The carbon is not from a natural fire. It is only found inside the sites. You don’t get natural fires inside the shelters,” she retorted. “Americans criticize WITHOUT KNOWING. The problem is not mine! The problem is theirs! Americans should excavate more and write less!”

Guidon challenged American archaeologists to come to the site, draw their own samples, and do their own tests. They refused.

When they couldn’t make her back down, US archeologists discredited, belittled, then ignored Guidon, her research, and her site. It simply never appeared in surveys of ancient settlements in the Americas. “Everybody has pretty much deep-sixed Guidon,” one noted American archaeologist commented.

But time, it seems, is on her side.

New finds in Chile and South Carolina

Tom Dillehay, an American archaeologist working at sites in southern and central Chile, found extensive evidence of human habitation there 18,000 years ago, 5,000 years before the supposed appearance of the “Clovis people.” Settlers on the Chilean coast built lodges, ate a variety of seafood, and used different kinds of seaweed for medicines. Presence of quartz and tar from other areas indicated either a trade network or a wide area of exploration. Even though Dillehay had painstakingly recorded every discovery and each step of the dating process, and used independent labs for verification, the established archaeological community initially refused to consider his conclusions. He had to spend ten years defending his findings, but thanks to his persistence, there’s now at least a bit of doubt concerning Clovis First.

Albert Goodyear, who has been working at the Topper Hill chert mine site in South Carolina since the 1980’s, ran into similar problems when he found a rich deposit of Clovis style points and then, much farther down, ran into a completely different set of hearths and tools. The deepest layers dated to 50,000 years old. Again, the archaeological community raged against the findings, making life so miserable for Goodyear that he considered leaving the field completely.

For scholars with a vested interest in preserving Clovis First, it simply wasn’t possible that there were settlements before Clovis. If so, all their work would be meaningless.

Santa Elina rock shelter and more

Then more news came from Brazil, including discoveries at Santa Elina rock shelter in central Brazil, where pierced bone ornaments made from giant sloths (photo) were dated over 23,000 years old. Like Pedra Furada, it too had rock art and evidence of occasional, seasonal use over thousands of years. A site in Uruguay yielded evidence of humans hunting giant sloths 32,000 years ago. Now, these finds are being lumped together with Guidon’s research, indicating a record of human habitation in the area at least 30,000 years old. Some suggest over 50,000 years old.

Other revelations have followed. But the most dramatic challenge has come from Steven and Kathleen Holen, who have long held the belief that people were in the Americas before 40,000 years ago. In a paper in Nature, they argue that break marks on 130,000 year old mastodon bones found in Southern California suggest hominins (ancestors of modern humans) did the butchering using stone tools, perhaps to get at the marrow or use the bones for tools. To illustrate their point, the Holens used rocks they found at the site to break open elephant bones.

The dust still hasn’t settled from the fracas over their claims.

Even more radical theories

As Niede Guidon said years ago, “I think it’s wrong that everyone came running across Bering chasing mammoths – that’s infantile. I think they also came along the seas.” Now in her 80’s and mostly retired, she hasn’t softened her tone at all. She currently maintains that people first arrived in South America from West Africa, perhaps as far back as 100,000 years ago.

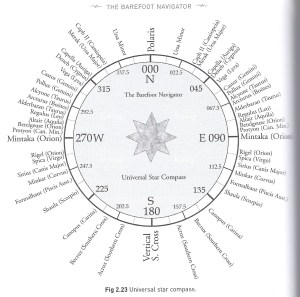

She says they could have floated or paddled across the sea with the current and the wind in their favor. Both journeys have been replicated in modern times. (The diagram at the left shows the route a 70-year-old Polish kayaker took in his solo journey across the Atlantic in 2017.) If you look at the globe, an African origin certainly makes more sense for settlements in northeastern Brazil than having people go through Alaska, down the coast of North America and Central America, then across the Andes and the Amazon Basin to get to Pedra Furada.

But Guidon isn’t stopping there. She suggests that the group from Africa may have merged with groups from the South Pacific that came by sea, settled on the Pacific coast and later crossed lower South America.

Evidence for the South Pacific theory

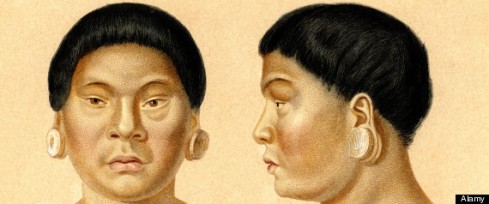

Several native populations in South America were completely eradicated by the Spanish and Portuguese conquerors. One group, the Botocudo, were murdered by the Portuguese because they wouldn’t submit to enslavement. Oddly, the Portuguese kept several of the skulls, which later wound up in a museum. When modern scientists drilled into the teeth and tested the DNA, they found markers typical of Polynesians and Australians. (Drawings of a Botocudo man, above). See earlier post on “Chickens, Sweet Potatoes, and Polynesians in Brazil.”

The Long Chronology

Increasingly, it looks as if there is no one simple answer to the origin or timeline of the peopling of the Americas. A new theory, called the Long Chronology, posits multiple waves of immigrants from different places arriving over a long period of time, probably with only a few successful, surviving settlements. This pattern seems more promising than Clovis First – and certainly more defensible given new discoveries. This does not rule out migration from Siberia or along the west coast of North America. It simply takes away its claim of exclusivity.

Serra da Capivara

Meanwhile, Niede Guidon is busy trying to get funding to keep the 320,000 acre national park she fought for, now called Serra da Capivara, open. (Entrance shown in photo.) Her research helped establish it as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1991, but government support is undependable. Few American archaeologists have ever visited. Only the hardiest tourists make the trip. But Guidon’s work is finally getting some attention from the press and the academic world. Robson Bonnichsen, from the University of Maine’s Center for the Study of the First Americans, feels her work needs more attention. “We’re trying to get some eminent American scholars down there to study the methods and results,” he said. He plans to lead the first American excavation team there.

This should be interesting to watch. Perhaps if an American man gets the same results, the data will get more respect. If so, Guidon will probably wonder what took the rest of the world so long to catch up with her.

Sources and interesting reading:

Bellos, Alex, “Archaeologists feud over oldest Americans, The Guardian, 10 February 2000, https://www.theguardian.com/science/2000/feb/11/archaeology.internationalnews

Bower, Bruce, “People may have lived in razil more than 20,000 years ago,” Science News, 5 September 2017, https://www.sciencenews.org/blog/science-ticker/stone-age-people-brazil-20000-years-ago

Bower, Bruce, “Texas toolmakers add to the debate over who the first Americans were,” Science News, 11 July 2018, https://www.sciencenews.org/article/texas-toolmakers-add-debate-over-who-first-americans-were

Brooke, James, “Ancient Find, But How Ancient?” 17 April 1990, The New York Times, https://www.nytimes.com/1990/04/17/science/ancient-find-but-how-ancient.html

Fenton, Bruce, “Brazilian rock shelter proves inhabited Americas 23,000 years ago” The Vintage News, 29 January 2018, https://www.thevintagenews.com/2018/01/29/brazilian-rock-shelter/

Guidon, Niede, “Nature and the age of the depostis in Pedra Furada, Brazil: Reply to Meltzer, Adovasio and others, Antiquity, vol.68, 1994. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/285362399_Nature-and-age_of_the_depostis_in_Pedra_Furada_Brazil…

“Interview with Niede Guidon,” Crosscultural Maria-Brazil, http://www.maria-brazil.org/niede-guidon.htm

Jansen, Roberta, “The archaeologist who fights to preserve the vestiges of the first men of the Americas,” BBC News, 12 March 2016, https://www.bbc.com/portuguese/noticias/2016/03/160312_perfil_niede_guidon_rj_ab

“Niede Guidon,” Wikipedia, https://en.eikipedia.org/wiki/NI%C3%A8de_Guidon

“Niede Guidon,” WikiVividly, https://wikivividly.com/wiki/Niede_guidon

“Pedra Furada,” Britannica Online Encyclopedia, https://www.britannica.com/place/Pedra-Furada

“Pedra Furada,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pedra_Furada

“Pedra Furada, Brazil: Paleoindians, Paintings, and Paradoxes, an interview with Niede Guidon and others, Athena Review, vol. 3, no.2: Peopling of the Americas,

Peron, Roberto, “Pedra Furada the Pierce Rock Site,” Peron Rants (blog) 28 April 2017, https://rperon1017blog.wordpress.com/2017/04/28/pedra-furada/

Powledge, Tabitha, “News about ancient humanity: Humans in California 130,000 years ago?” PLOS Blogs, 5 May 2017, http://blogs.plos.org/onscience blogs/2017/05/05/news-about-ancient-humanity-humans-in-California-130000-years ago…

“The Rock Art of Pedra Furada,” The Bradshaw Foundation, http://www.bradshawfoundation.com/south_america/serra_da_capivara/pedra_furada/index.php

Rock Art panel, photo by Diego Rego Monteiro – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=43861884

Romero, Simon, “Discoveries Challenge Beliefs on Humans’ Arrival in the Americas,” The New York Times, 27 March 2015, https://www.nytimes.com/2014/03/28/world/americas/discoveries-challenge-beliefs-on-humans-arrival-in-the-americas.html

“Serra da Capivara National Park,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Serra_da_Capivara_National_Park

Wade, Lizzie, “Traces of some of South America’s earliest people found under ancient dirt pyramid,” Science, 24 May 2017, http://www.sciencemag.org/news/2017/05/traces-some-south-america-s-earliest-people-found-under-ancient-dirt-pyramid

Wilford, John Noble, “Doubts Cast on Report of Earliest Americans,” The New York Times, 14 February 1995, https://www.nytimes.com/1995/02/14/science/doubts-cast-on-report-of-earliest-americans.html