On one episode of the PBS show History Detectives, April Hynes of Washington Crossing, Pennsylvania brought in a small ceramic jug to be evaluated by antiques experts. It was discovered in the 1950’s by her grandfather, a plumber working in Germantown, Pennsylvania, who thought it might be an Indian piece, so he took it home. It has remained with the family ever since.

The jug is about 6” tall, with a greenish-brown glaze. (See photo) Its most striking feature is the face on it. The eyes are round and staring, and the mouth is open, exposing clenched teeth.

In the course of the show, experts from the Philadelphia Museum of Art and art historians examining the piece concluded it was not an American Indian artifact. Instead, it was very similar in size, design, and glaze to jugs made in the 1850’s and 1860’s by slave potters on Edgefield County, South Carolina plantations.

Jekyll Island and The Wanderer incident

Many of those slaves were brought from the Congo through ports in Angola and imprisoned on slave ships bound for North America. Some of those who survived the voyage were “processed” through Jekyll Island, off the coast of Georgia and worked on plantations on the South Carolina side of the Savannah River, including the Edgefield plantations.

Ironically, Jekyll Island is today a lovely place, home to upscale vacation resorts, like the one in the photo above. Its blood-soaked history has been largely ignored. The Jekyll Island Club Hotel “Island History” handout dedicates a short paragraph to the 19th century, saying:

“Slaves were imported to pick cotton, which was the primary agricultural product on the island during this time. The U.S. government banned the importation of slaves in 1807, but smuggling still continued. On November 29, 1858, The Wanderer unloaded 409 slaves on Jekyll Island, one of the last cargoes of slaves imported into the United States. Those involved in the activities of the Wanderer were indicted by the federal government.”

The racing yacht The Wanderer refitted as a slave ship, shown in the oil painting above.

That’s the end of the 19th century history section. But what the Jekyll Island Club Hotel piece fails to include is that the slave traders were never convicted, despite three attempts by the federal government. Outcry over The Wanderer slave trading trials helped fuel anti-slavery sentiment in the north, including support for the Underground Railroad and the Civil War.

In yet another bizarre chapter of its history, in 1859, The Wanderer, which was not a standard slave trade ship, having been built as a racing yacht originally, was apparently taken on one more slave trading voyage after the trials, despite the fact that slave trading had been illegal for fifty years by then. However, near the coast of Africa, the first mate led a mutiny, set the captain out to sea in a small boat, and returned the ship to Boston. During the Civil War, the U.S. government seized the ship and used it as a gunboat in the blockade of the South.

Further, J. Egbert Farnum, (photo, left) who had been a hot-headed, hard-drinking officer on The Wanderer on its infamous 1858 voyage, later regretted his part the affair and headed north after being acquitted. When the Civil War broke out, he signed up with the Northern Army to make amends. He later suffered nineteen bullet wounds and two saber wounds.

Further, J. Egbert Farnum, (photo, left) who had been a hot-headed, hard-drinking officer on The Wanderer on its infamous 1858 voyage, later regretted his part the affair and headed north after being acquitted. When the Civil War broke out, he signed up with the Northern Army to make amends. He later suffered nineteen bullet wounds and two saber wounds.

The ship’s story sounds like a movie plot.

But back to the strange little pot uncovered near Philadelphia.

In the PBS show, David Barquist, curator of American Decorative Arts at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, confirmed what April Hynes had discovered – that face jugs were generally associated with slave potters in Edgefield County, South Carolina. Barquist went on to say that only a dozen or so of the original face jugs have been discovered. Most are now in museums or private collections. (The one pictured below right is from the collection of the Milwaukee Art Museum.)

The grimace and green-brown ash glaze are typical of face jugs made in Edgefield during the 1850’s and 1860’s. Jim McDowell, a potter who continues the face jug tradition using 19th century techniques he learned from his Jamaican ancestors, showed how the face would be created and attached to the jug. When he was asked how the jugs were used, McDowell said they probably were not used to carry water. Instead, they were used as grave markers since slaves were not allowed to erect stone markers.

Indeed, shards of face jugs have been found in slave burial grounds.

Fusion of Old and New Beliefs – Ancestor worship, Voodoo, and Christianity

The face jug featured in the show carries a long cultural tradition behind it. It represents West African beliefs put into a form outsiders could not recognize – or forbid. It served as more than a grave marker to people who were not allowed to erect grave markers. Face jugs became containers for holding and guarding a precious connection with the past.

Wyatt MacGaffey, author of Kongo Political Culture: The Conceptual Challenge of the Particular, explains that power comes from the land of the dead, and in precolonial times, was present and available for use in minkisi: fabricated items that provide local habitations for the dead, throu gh which the powers of such spirits are made available to the living. Minkisi typically include clay, stones, or grave dirt. A Nkisi, singular form of Minkisi, power figure from the Congo is pictured, left.)

gh which the powers of such spirits are made available to the living. Minkisi typically include clay, stones, or grave dirt. A Nkisi, singular form of Minkisi, power figure from the Congo is pictured, left.)

Thus, the jug, especially when it contained dirt from the grave, became a powerful item, very similar to the ritual baskets popular in parts of West Africa, which contained teeth, hair, or bone fragments of the dead person. These items link the dead to the living, making an unbroken lifeline, which would have been especially important to people who had been wrenched away from their homeland. The ancestors, as represented by the face jugs, are then part of life and ceremonies, and can be consulted on matters of importance. Also, they lend considerable strength.

Spirit objects

It seems clear that these small jugs were portable representations of the dead and their power. As Gary Dexter, an Aiken, South Carolina potter and historian remarked, “Obviously, this [the face jug] was the single most important cultural item they had.”

The big question for the people in the TV show was how the face jug wound up near Philadelphia if it was made in South Carolina, 700 miles away.

The Underground Railroad

If the jug was owned by a slave, which seems to be the case based on studies of other jugs of similar size, design, and construction, it could have been carried north during the owner’s attempt to escape to free territory. Philadelphia was a hub for those trying to get to Canada and freedom. (See map below, which shows Philadelphia as part of one route.)

The Underground Railroad was a series of safe shelters for runaway slaves. They were often private homes run by people who abhorred slavery and sought to help as many slaves as possible escape that fate. The Lemoyne House in Washington, Pennsylvania was one such stop. The Mother Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church, the oldest AME church in the United States, was another. In Germantown, the area of northwest Philadelphia where the face jug was buried, there were several safe houses. The whole area was predominantly anti-slavery, mostly due to the influence of the Society of Friends (Quakers), so if escaped slaves could get there, chances were good they could find a place to rest.

Finding the pot buried in Germantown points to the owner being an escaped slave. Unfortunately, we have no way of knowing why the precious artifact was buried, so the story remains unfinished.

“Memory bottles”

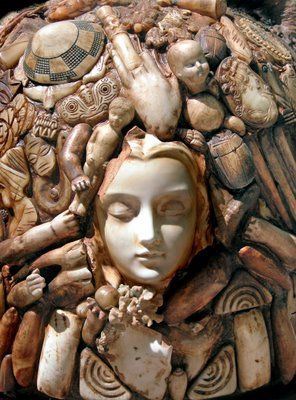

The influence of slave-made face jugs spread far beyond the slave communities. In the 1800’s, memory bottles or “spirit jars” became popular across North America. A thick layer of putty, lacquer, plaster, clay, or cement added to the bottle or jug held the various charms, mementos, and decorations that were reminiscent of the deceased loved one. Some of them look surprisingly like the African spirit figures of long ago. (A Midwestern “memory bottle” is on the left, an African Nkisi figure on the right in the photos below.)

Memory bottles enjoyed a Renaissance in the 1950’s and 60’s, especially in the Midwest and Appalachia, crossing racial lines. Currently, both E-bay and Etsy do a lively business in both antique and modern memory bottles. The one on the left (below), advertised on Etsy, seems to have its own bizarre power. The one on the right was made in memory of a member of the clergy.

Death, power, and memory combined: the legacy of the original face pots.

Sources and interesting reading:

Bradley, Eric. “10 Things You Didn’t Know about Memory Jugs,” 24 February 2011, Antique Trader, http://ww.antiquetrader.com/articles/feature-stories/ten_things_about_memory_jugs

“Destination Freedom: Traveling PA’s Underground Railroad Pennsylvania,” Visit PA, http://www.visitpa.com/articles/destination-freedom-traveling-pas-underground-railroad

“Face Jug” episode of History Detectives, Season 8, episode 8, PBS, 2010 www.pbs.org/historydetectives

“Face jug,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Face_jug

“Germantown, Philadelphia,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Germantown_Philadelphia

“History of the African-American Face Jug” The Black Potter: Face Jugs and Functional Pottery, http://www.blackpotter.com

Hynes, April. “Farnum,” The Wanderer Project, 15 June 2012, https://thewandererproject.wordpress.com/2012/06/15/farnum/

“Island History,” Jekyll Island Club Hotel, http://www.jekyllclub.com/about-us/island-history/

MacGaffey, Wyatt. Kongo Political Culture: The Conceptual Challenge of the Particular. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press, 2000.

“Matt Jones Pottery – Face Jugs,” http://jonespottery.com/face-jugs/ This source includes photos of grotesque face jars that are little more than racial slurs made into pottery, but it also includes some modern face jugs that carry on the African tradition.

“Nkisi,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nkisi

“Nkisi Nkondi, Kongo people,” Central Africa: Democratic Republic of the Congo, KHAN Academy, https://khanacademy.org/humanities/art-africa/central-africa/democratic-republic-of-the-congo/a/nkisi-nkondi

Osborne, John, reporter. “In Charleston, South Carolina, all charges in the Wanderer slave ship case are dropped,” report on federal trial of J. Egbert Farnum and others, as recorded in Tom Henderson Wells’ book, The Slave Ship Wanderer.

“Reliquary Guardian Figures,” Central African Art: A Personal Journey, from the Lawrence Gussman Collection, http://africa.si.edu/exhibits/journey/guardian.html

Richman, Jeff. “Green-Wood Connections Everywhere!” Green-Wood Historian Blog, 29 October 2009, https://www.green-wood.com/2009/green-wood-connections-everywhere-2/

“Ritual Pottery from Togo and Benin,” Arte Magica Galerie, http://www.artemagica.nl/Ritualpottery

“Slave Pottery: Face Jugs” US Slave (blog), http://usslave.blogspot.com/2012/05/slave-pottery-face-jugs.html

“South Carolina Plantations: Edgefield County, SC Plantations,” SCIWAY: South Carolina Information Highway, http://south-carolina-plantations.com/edgefield/edgefield-county.html

“The Underground Railroad: A Well-Kept Secret,” ArtSmart Indiana, http://www.artsmartindiana.org/resources/ugrr.php

“Underground Railroad Map,” American Historama, http://www.american-historama.org/1829-1841-jacksonian-era/underground-railroad-map.htm

“Unusual Vintage African Mask – Republic of Congo, for sale on Quintessentia, http://www.quintessentia.com/art/africana/unusual-vintage-african-mask-republic-of-congo-9.html

“Vodun (aka Voodoo) and related religions,” Religious Tolerance: Ontario Consultants on Religious Tolerance, http://www.religioustolerance.org.voodoo.htm

“Wanderer (slave ship)” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wanderer_(slave_ship)

Well, Tom Henderson. The Slave Ship Wanderer. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 1967.

“West African Vodun,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/West_African_Vodun

“Wooden Nkongi Fetish Statue,” from the Pinterest board “Togo” https://www.pinterest.com/angsor1/togo

Thanks. I knew nothing about face jugs until I began reading this. Very interesting history.

Thanks, Ron!