Bloodletting, Sacrifice, and Rebirth

As covered in the previous post on the subject, https://misfitsandheroes.wordpress.com/2017/03/06/its-not-an-alien-astronaut/ the famous sarcophagus of K’inich Janaab’ Pakal, or Pakal the Great does not show an alien astronaut. It represents the King, who died in 683 CE, after ruling for 68 years.

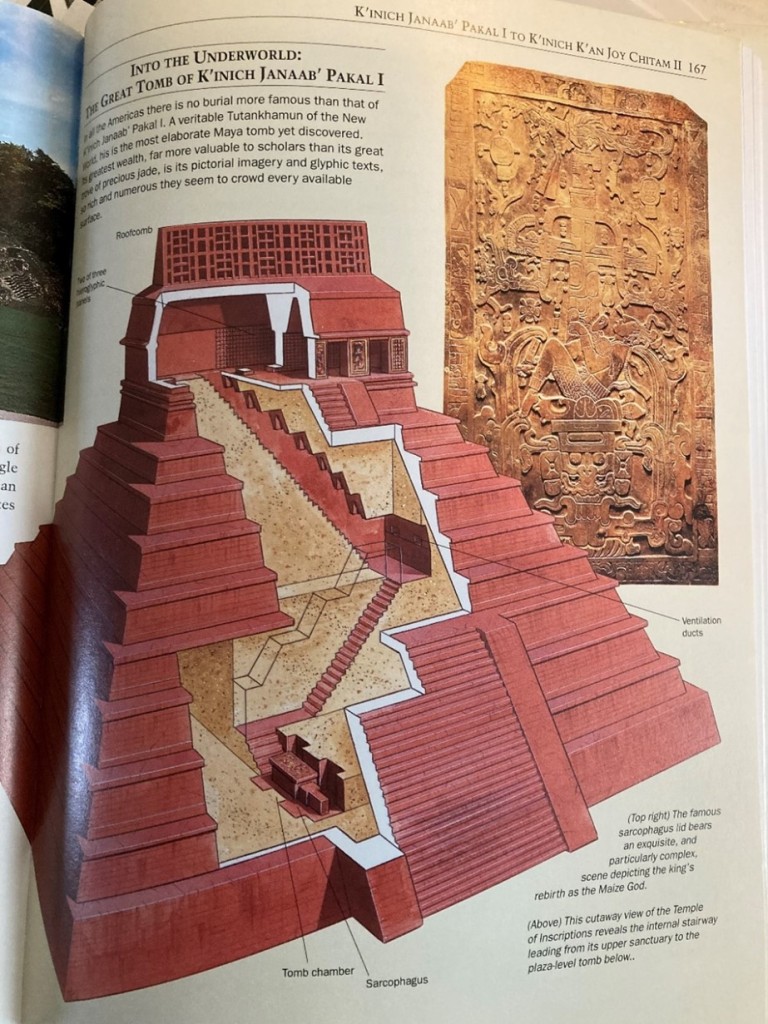

As indicated in the illustration from Chronicle of the Maya Kings and Queens, the sarcophagus lies deep inside the Temple of Inscriptions, where it was discovered in 1952. Unfortunately, archaeologists at that time were not able to translate the many symbols and glyphs on the sarcophagus.

Von Danniken’s alien astronaut theory was simply an elaborate guess, supported by common science fiction themes of the time.

What’s more interesting is what it actually means. The carving on the sarcophagus is an extraordinarily beautiful presentation of Maya beliefs about the cosmos, the king, bloodletting, and rebirth.

Maya symbols and cosmology

The World Tree

Maya cosmological beliefs, many of which were absorbed from earlier cultures, were fairly consistent across the Maya city-states. They saw the world as divided into three zones: The Upper World, or the land of the gods, the Middle World, where humans live, and the watery Underworld, the realm of death. The World Tree, the axis mundi, spanned all three worlds.

It took many forms, including a Ceiba tree, a stylized maize (corn) plant, and a cacao tree. That is the cruciform image you see at the center of the sarcophagus carving.

The illustrations above show two different panels from Palenque, both showing the World Tree in the center. One uses a design like the one on the sarcophagus lid, but the other makes the maize plant itself the World Tree, complete with personified ears of corn. Note that Itzamna still appears at the top, the Underworld monster appears at the bottom, but the bloodletting tools are omitted and the arms of the World Tree are branches of the maize plant rather than blood scrolls.

Bloodletting

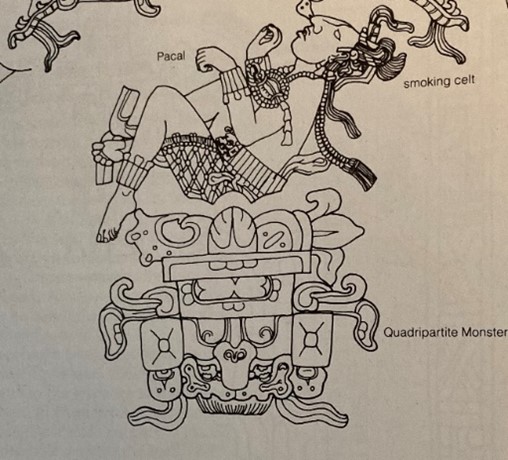

On the sarcophagus lid, Itzamna, the creator god, shown as the Celestial Bird, perches at the top. Right below it is a blood scroll and a bloodletting bowl. The sign for mirror/shining appears on the bowl and several times on the tree itself.

Under the figure of Pakal is another bloodletting bowl (outlined in red in my illustration) marked with the “kin” or day/sun sign (marked in green) and topped by the tools of bloodletting: an obsidian lancet, a stingray spine, and the symbol for death, balanced by new maize growth on the right side.

You can see a similar arrangement of bloodletting bowl and tools in the top of the headdress of a ruler in a stela at Copan, in northern Honduras (middle illustration above). Again, the bowl is marked with the kin sign, but in this image, the cross sky bands appear on the left, the stingray spine in the middle, and the obsidian blade on the right.

The Royal Duty

Bloodletting was considered the duty of Maya royalty, both men and women. The gods made humans from maize and blood, and they needed regular infusions of blood to keep the world going. A ruler’s blood gift allowed the entire community to thrive. It provided “ch’ulel,” the soul-stuff of the universe. The illustration on the left above shows a blood-spattered cloth in an offering bowl.

A famous carving from the Maya city of Yaxchilan (detail and full lintel above) shows the queen drawing a barbed rope through her tongue. The blood drips down the rope to the bowl. Note the shape of the bowl and similarity to the images on the sarcophagus lid.

The king was expected to undergo ritual bloodletting from his tongue, ears, or genitals.

The section of a panel from the Bonampak (Mexico) site in the middle of the two images above shows one of the gods impaling himself to provide the blood needed for creation. A sacrificed deer is shown on the right. The blood scrolls fertilize the World Tree.

Bloodletting tools were considered so important they were often interred with the dead.

Pakal and the Maize God

On the sarcophagus lid, Pakal is shown at the moment of his death falling down the World Tree toward the Underworld, the land of the dead, marked by the Earth Monster with its skeletal jaw and death signs. Yet the image is not one of an old man dying. Pakal appears as a young man, specifically the young Maize god (statue, right). His hair style, dress, even hand gestures identify him.

Pakal is becoming a sacrifice and undergoing a transformation – dying and being reborn as a god. His hands are bound, but the turtle symbol that is tied to them represents the rebirth of the Maize god from the shell of a turtle. The position of his legs mimic the “unen” or baby sign.

His death is a creative act. His blood will fertilize the sacred tree at the center of the world, and he will be reborn.

Ancestors and nobles

Pakal is not alone in his journey.

All along the border on the outside of the lid are references to celestial bodies and six portraits of leading nobles. The coffin inside the sarcophagus is carved on all four sides with portraits of Pakal’s ancestors emerging as trees sprouting from the ground, marked by the swirling earth sign below the figures. Painted stucco figures on the walls of the tomb echo these references to relatives and important figures in the life of the leader who was laid to rest in the tomb.

Apparently, the artists responsible for the paintings of the ancestors ran short of time, for some of them remained unfinished when the King died.

Thoughts

The image on Pakal’s sarcophagus lid does not show an alien astronaut. It tells a complex story of a human ruler dying and falling into the Underworld, but like the maize seed, he is being buried in the earth only to rise to a new life. He is both falling down the World Tree and rising back along it.

He is presenting his death as the ultimate blood offering and sees himself being reborn as the Maize God. Those of you familiar with Christian beliefs about the death of Jesus Christ as the offering required to save the world will find interesting echoes here.

Sources and interesting reading:

Baudez, Claude-Francois. Maya Sculpture of Copan: The Iconography, Norman and London: University of Oklahoma Press, 1994.

Coe, Michael and Mark Van Stone. Reading the Maya Glyphs. London: Thames and Hudson, 2001.

Martin, Simon and Nikolai Grube. Chronicle of the Maya Kings and Queens: Deciphering the Dynasties of the Ancient Maya. London: Thames and Hudson, 2000. An excellent source.

Miller, Mary Ellen. Maya Art and Architecture. London: Thames and Hudson, 1999

Montgomery, John. Dictionary of Maya Hieroglyphs. New York: Hippocrene Books, 2002

Montgomery, John. How to Read Maya Hieroglyphs. New York: Hippocrene Books, 2002

Schele, Linda and David Freidel. A Forest of Kings: The Untold Story of the Ancient Maya. New York: Quill, William Morrow, 1990.

Schele, Linda and Mary Ellen Miller. The Blood of Kings. New York: George Braziller, Inc in association with Kimbell Art Museum, 1986. An excellent source.

Stone, Andrea, and Marc Zender. Reading Maya Art: A Hieroglyphic Guide to Ancient Maya Painting and Sculpture. London: Thames and Hudson, 2011

All illustrations used in this post are taken directly from the books listed.

Thank you, Kathleen Rollins, for the Mayan information.

Ron Fritsch

Thanks, Ron. I always appreciate your feedback.