Sacrifice, as we usually understand the concept, is purposeful giving up. It may be as simple as foregoing chocolate or alcohol during Lent or as difficult as killing humans or animals for what is perceived as the greater good.

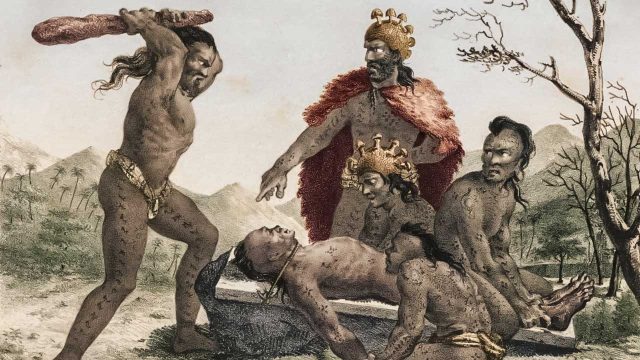

Ancient people practiced human sacrifice in many different areas, including Africa, Europe, South America, Central America, North America, the Near East, Austronesia, and the Far East. These sacrifices generally served either to please the gods or to honor prestigious humans who wanted a group of people to accompany them into the afterlife. According to Joseph Watts and his colleagues at the University of Auckland in New Zealand, when Pacific Island chiefs beheaded their more helpless rivals, the act helped to create a sense of social stratification and control.

But usually, when we think of human or animal sacrifice, we think of offerings to the gods, which is curious in itself. The photo shows an Inca mummy left out on the mountains as an offering to the spirits.

Why did people use sacrifice to contact their gods and affect the course of events? Let’s start with what we know and work our way backwards in time.

Blood: the fluid of life

For the ancient Maya, blood, the fluid of life, was the most valuable substance that people could offer the gods. Blood offerings kept the world turning and the gods appeased. The more valuable the offering, the more worthy the sacrifice.

Like the Olmecs before them, the Maya sacrificed both animals and humans. Animals included crocodiles, iguanas, dogs, jaguars, and turkeys. Human sacrifice, however, was seen as more valuable. As Ethan Watrall, Assistant Professor at Michigan State University explains, “It [Sacrifice] has been a feature of almost all pre-modern societies during their development and for mainly the same reason: to propitiate or fulfill a perceived obligation toward the gods.”

Beheading appears often in Mayan literature, including the Hero Twins creation story recorded in the Popul Vuh, sometimes called the Mayan Bible. The picture included here shows a stone panel from Chichen Itza showing one of the Hero Twins (on the right) after he has been decapitated during a ballgame with the Lords of the Underworld. His head, used as the ball for a while in the game, appears in a circle to the left of the twin who is spurting rivers of blood from his neck.

However, death is a temporary state in the Popul Vuh, and the twin who was decapitated later gets his head back later in the story. Still, the Hero Twins show themselves to be quite willing to play with death, literally, in the form of the Lords of the Underworld with all their potent magic.

Recent finds at Tonina, in Chiapas, Mexico, indicate that it was known as the City of Divine Captives. The beheading of two sons of rival ruler Pakal from Palenque is memorialized in stone at the site. (See photo.) The captives, with their hands bound behind them, slump in defeat. But according to the beliefs of the time, spilling their royal blood would increase the prosperity of Tonina and help keep the cosmos alive.

This seems hard for us to understand. Today people feel little connection with or obligation to the natural world, but sacrifice was once perceived as the way to keep the world going. The movement of the sun, moon, and stars, the abundance of land and sea animals, the continuation of life itself depended on the active participation of people. If they stopped giving gifts to the gods, everything stopped, and disaster followed.

This belief may have been the result of apparent causality: people stopped offering sacrifices to the gods and then something terrible happened. It could also carry the weight of tradition. We’ve always killed a young woman to make the crops grow, so we better not change.

Righting a wrong

Sometimes, sacrifice is a means of righting a wrong. In that case, the ancient people had to have an awareness of sin – a moral transgression that required a moral gift to the gods to erase it.

The French philosopher Georges Bataille maintained that it was the consciousness of transgression that defined modern humans and separated them from the animals. To make amends for their sins, people offered sacrifices to the gods, including the spilling of human blood.

But sacrifice is more complicated than righting wrongs. It also served as a way to acknowledge and worship the gods, to make a request, or to give thanks, or perhaps all of the above.

Animal sacrifice

The Greek sculpture from the Louvre collection, pictured, shows the sacrifice of a boar to the gods. (Photo, below)

In order to gain God’s favor, believers of many ancient faiths regularly sacrificed animals, perhaps because killing humans dangerously depleted their population after a while, especially if they kept sacrificing the best. So certain animals may have become the stand-in for people. In some cases, the animals were cooked and parts were eaten in a sort of communal feast with the gods. The books of Exodus and Leviticus in the Old Testament give clear directions on the kinds of animals (such as a bull, lamb, goat, or dove) to be sacrificed for each kind of sin and the portions the priest and the faithful should eat. Each explanation includes the reassurance that God will find the aroma of the burnt offering pleasant. “It is a burnt offering, an offering made by fire, an aroma pleasing to the Lord” (Leviticus 1:12).

Biblical scholar Alice C. Lindsey maintains that animal sacrifice as defined in the Old Testament came from much older societies, including older Mesopotamian civilizations, such as the Kushites. Nimrod, the son of Kush, moved to the Tigris-Euphrates valley and established the practice of sacrificing rams, bulls, and sheep. Abraham was a descendant of Nimrod.

To be a suitable sacrifice, the animal had to be perfect, and the person sacrificing the animal had to identify with it at the moment he took its life. If these conditions were met, the guilt would be transferred to the innocent animal, the sacrifice would be pleasing to God, and the act of spilling its blood would bring purification to the supplicant in particular and the society in general, by transference. “Without the shedding of blood, there is no forgiveness” (Hebrews 9:22). The more valuable the animal, the more valuable the sacrifice.

As a cautionary note, the book of Leviticus includes the story of two of Aaron’s sons who decided to make their own offering by burning incense before the Lord, contrary to His command. “So fire came from the presence of the Lord and consumed them, and they died before the Lord” (Leviticus 10:2). Clearly, death is the punishment for straying from the correct path.

Older models of animal sacrifice

But the practice of animal sacrifice is far older than the events recorded in the Old Testament. Vedic Hindu teachings of ancient India use the word bali to mean tribute, offering, or the blood of an animal, which might be a horse (symbol of the cosmos) a goat, a bull, an ox, a chicken, or a calf. Later, for Hindus, the cow became the revered symbol of all life, and of Earth, the nourisher of life, the representative of Kamadhenu, the divine, wish-fulfilling cow, and as such merited protection. Interestingly, the cow was also the symbol of Hathor, the ancient Egyptian goddess of love, joy, and motherhood, usually depicted as a sacred cow or a woman with a cow-horn headdress.

Also consider the famous San paintings in South Africa which feature dancing men surrounding the “dream beast,” the eland, the favorite animal of the gods. The men are dream-hunting the dream-beast that controls the rain. When the beast bleeds, rain falls. In the most famous panel, from the Game Pass Shelter in Drakensburg, the shaman imitates the eland, standing behind it, his legs crossed the same way the eland’s are, bleeding from t he nose just as the dying eland is. Again, this shows a sort of ritual sacrifice.

he nose just as the dying eland is. Again, this shows a sort of ritual sacrifice.

The ultimate sacrifice and gift, according to the Bible

In the Bible, human sacrifice at God’s request is the ultimate test of faith. The most famous example in the Old Testament is God asking Abraham to sacrifice his son Isaac. (In the Koran, the son is not named but many Muslims believe it to be Ishmael.) In obedience, Abraham prepares the pyre.

At the last moment, an angel stops Abraham and shows him a ram he can sacrifice instead of his son. (Interestingly, the ram, like the bull, is a common choice for sacrifice.)

The heart of the New Testament is the sacrifice of Jesus, whose death Christians feel liberates them from their heritage of sin. In the Catholic mass, the priest pours a little water into the wine in the chalice then lifts the bread and wine as an offering to God. He then ceremonially washes his hands, just as priests and rabbis did before ritual slaughters. The priest then says, “Pray, brethren (brothers and sisters), that my sacrifice and yours may be acceptable to God, the Almighty Father.” In the old version of the Catholic mass, the Latin wording translates as “Come, O Sanctifier, Almighty and Eternal God, and bless this sacrifice prepared for the glory of Your holy name.” The consecrated bread becomes, for the faithful, the body of Christ. The wine becomes the blood of Christ. The faithful then consume both, in order to share in the sacrifice and the redemption it promises.

Symbolic human sacrifice

When I was helping on an archaeological dig of an early Maya site in Chocola, Guatemala, workers found a small statue of a bound, beheaded captive included in the foundation of a building. Along with the metates (grinding bowls) and intentionally smashed cookware also included in the foundation, archaeologists interpreted the figure of the captive as a dedicatory offering to the gods.

The Chocola figure struck me as interesting because it was a symbolic blood sacrifice, a clay figure that took the place of a human.

Today, many Christians keep a crucifix on the wall, remembering the sacrifice of Jesus Christ, known as the Lamb of God, on the cross. Like the Chocola figure, this statue symbolically replaces the ultimate human/divine sacrifice.

So the idea of ritual sacrifice is wide-spread, but where did it come from?

A triple burial found in Moravia and dated to 27,000 years ago may provide some clues. In the grave, three adolescents are laid out so one is facing down while the other two face each other. The figure on the left in the photo (below) is apparently reaching over to the genital area of the one in the middle, who was affected by congenital dysplasia. Since the bodies seem to have been purposely arranged, the site brings up many unanswered questions. Why were these three buried together? What was their relationship? Were they killed?

Two other Paleolithic graves, in Italy and Russia, also contained adolescents with deformities. As part of their burial, they were decorated with ivory beads, which would have been very valuable.

Archaeologists investigating a series of graves dating from 26,000 to 8,000 BC found several that contained the remains of young people who suffered from abnormalities, including extra fingers and toes. In an article in Current Anthropology, Vincenzo Formicola of the University of Pisa, Italy, maintains that these burials could be a sign of ritual killing because, unlike usual burials, with a single body, these sites often contain multiples. “These individuals may have been feared, hated, or revered,” Formicola said.

Perhaps, because they were different, they were both feared and revered as different and therefore “touched by spirits.”

Back to the “Venus” Figurines

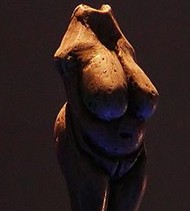

One of the most enduring enigmas in Western art is the popularity of the “Venus Figurines,” the small sculptures of obese, exaggerated female figures that appear in different sites from the Mediterranean to Siberia, over an enormous span of time, from the Venus of Hohle Fels (Germany), about 40,000 years old, to the Venus of Garagino (Ukraine), about 22,000 years old. The illustration shown here gives a sampling of the “Venus” figures found.

In most cases, the female figures are small and thus portable. While many have wildly exaggerated breasts and buttocks, and sometimes a pregnant belly, they have little or no face or feet, and sometimes no arms. Many writers have pointed to these early figurines as evidence of a widespread “Goddess Cult.”

The problem is, many look more like sacrifices than gods, though I suppose the two entities can be combined.

Take the “Venus” of Gagarino figure, (photo, left) one of several found in the Voronezh region of Russia, in the same region as the Kostenki and Avdeeno sites (22,000 years old), which have also yielded extensive finds of bone awls and points, burnishers, shovels, and jewelry. Gagarino yielded several Venus figures. The one pictured was found buried in a prehistoric fire pit. It has a featureless round head, enormous breasts, and an undefined lower body.

Take the “Venus” of Gagarino figure, (photo, left) one of several found in the Voronezh region of Russia, in the same region as the Kostenki and Avdeeno sites (22,000 years old), which have also yielded extensive finds of bone awls and points, burnishers, shovels, and jewelry. Gagarino yielded several Venus figures. The one pictured was found buried in a prehistoric fire pit. It has a featureless round head, enormous breasts, and an undefined lower body.

The Venus of Moravany (photo, right), from about the same time period (23,000 years ago), was found in Slovakia. Like many others, it was purposely beheaded before being buried.

Willendorf Venus

The famous Venus of Willendorf (Austria), perhaps the most well-known European Venus statue (24,000 years old), has sometimes been described as a celebration of fatness and therefore plenty, but she doesn’t look as if she’s celebratin.(photo, left). With her bowed head and stooped shoulders, she looks like the victims at Tonina, Mexico.

The Venus of Lespugue (France) is even older and her features more exaggerated. Again, her head is bowed.

The oldest European Venus statue, the Venus of Hohle Fels (Germany), dated to 35,000 years ago, has a huge middle, a tiny suggestion of a head, and no feet.

Many sources, including the program “How Art Made the World” on PBS, have called these statues a statement of exaggerated beauty. The site called About Archaeology describes these statues as “Rubenesque,” but Rubens never painted women like these: faceless, footless, sometimes armless figures with hunched shoulders and bowed heads. Their creation, neuroscientist V. S. Ramachandran argues, shows that ancient artists valued the parts of the female that were most attractive and important: breasts and pelvic girdle.

However, other statues of females — not wildly exaggerated — have been found at these Paleolithic sites, as have statues of males, and many animal figures. What’s interesting is that most of the pieces found ritually destroyed and buried are of grossly exaggerated females. Why?

A couple of theories

A sacrifice to get rid of a problem

Like the ritually killed and buried people with abnormalities found in Eastern Europe, it’s possible that the Venus figurines represented diseased females. Elephantiasis, lymphedema, tuberculosis, leprosy, or podoconiosis would cause gross enlargement of the breasts and genitals. Genital elephantiasis can also be caused by sexually transmitted diseases, such as Chlamydia. Today, where women are affected by elephantiasis, they are socially shunned. Ironically, despite their swollen female features, they typically have trouble getting pregnant.

If this were the case in an ancient society, these women may have been ritually sacrificed. That would explain the ropes tying the Venus of Kostenki’s wrists and her missing head. It would also explain the many cut marks found on all of these figures. And perhaps the unusual clothing, including net or knitted headwear.

A sacrifice to avoid a problem

If the statues were a stand-in for a human sacrifice that would address some problem, even if it wasn’t disease-related, it’s likely the idea would spread quickly. In order to avoid these problems in your tribe, you could simply ritually kill a little statue. It could become part of the process of setting up a village or a dwelling, the way some people tack up a horseshoe over the garage – or the way the ancient Maya included the statue of a beheaded, bound captive in the foundation of their building.

A sacrifice to create life

Another possibility is the statue represents a female creation figure who must be destroyed for life to emerge, like the Aztec creation goddess, Coatlicue (She of the Serpent Skirt, pictured, left) and her daughter Coyolxauhqui (pictured below, right, after she was torn apart to create the world).

Another possibility is the statue represents a female creation figure who must be destroyed for life to emerge, like the Aztec creation goddess, Coatlicue (She of the Serpent Skirt, pictured, left) and her daughter Coyolxauhqui (pictured below, right, after she was torn apart to create the world).

Spanish explorers discovered a statue of Coatlicue in 1790, near what is now called the Calendar Stone or Sun Stone, in Mexico City. She wears her skirt of snakes and a necklace of skulls. Her hands and feet have claws so she can devour her prey. (She was considered so frightening at the time that the statue was re-buried.) She is the destructive force that both gives life and takes it away. Her hair hangs down her back in 13 plaits, symbolic of the 13 lunar months and 13 heavens of Aztec religion.

That does make you wonder about the 13 marks on the horn (or crescent moon) held up by the Venus of Laussel (about 28,000 years old) discovered in the Dordogne Valley of France.

The problem is that nothing about the “Venus” figures suggests that kind of dark strength – or any kind of strength. With their hunched shoulders and downcast head, they seem powerless.

This is not to suggest that there was never a Goddess Cult, but only that the well-known Venus figurines were probably not representative of one. Certainly, though, some later figures in ancient Near Eastern and Mediterranean art depict powerful female figures. Inanna, Tanit, Astarte, Ishtar, Sekmet, Hathor and Isis were powerful goddesses with a huge following. (See the earlier post on them at https://misfitsandheroes.wordpress.com/2013/08/20/missing-fierce-powerful-goddess/)

The Venus figures, though, look more like sacrifices.

The question remaining is why this particular strange figure became the perfect symbolic sacrifice, copied, with variations, over an area ranging from current day Spain all the way to Russia! Perhaps it became a trade item or a gift, suggesting a sharing of powerful charms and therefore a social network. At some point in this sharing, she may have gone from an unfortunate victim to a magical one.

In any case, this statue apparently held enormous power.

Intriguing connections with Sudan, Siberia, and Indonesia wait to be explored. It’s also not clear what relationship, if any, the Berekhat Ram Venus figure (Golan Heights, 250,000 years old) has with the later sculptures of voluptuous females. Perhaps more research will help us fill in the blanks between them. It will be interesting to see what new facts we can learn about the sacrifices that were so central to our ancestors’ life.

Sources and interesting reading:

“Avdeevo: a Paleolithic site with strong links to Kostenki,” Don’s Maps, http://donsmaps.com/avdeevo.html

Baudez, Claude F. and Peter Mathews, “Captive and Sacrifice at Palenque,” Mesoweb. http://www.mesoweb.org/ari/publications/RT04/Capture.pdf

Benson, Emily. “Human sacrifice may have helped societies become more complex,” Science Magazine, April 2016, http:///www.sciencemag.org/new/2016/human-sacrifice-may-have-helped-societies-become-more-complex

Cartwright, Mark. “Coatlicue,” Ancient History Encyclopedia. November 2013, http://www.ancient.eu/Coatlicue/

“The Catholic Worship Service: The Mass,” http://www.dummies.com/how-to/content/the-catholic-worship-service-the-mass.html

Coffee, Albert. “New Discoveries at Tonina!” Albert’s Archaeoblog, July 2015, http://albertcoffeetours.com/blog/

“Elephantiasis” National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD) 2009, http://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/elephantiasis/

“The First Artists,” Exhibit at the Israel Museum, Jerusalem, http://www.imgf.org.il/exhibitions/presentation/exhibit/?id=358

Haviland, Willam A., et al. Anthropology: The Human Challenge. Belmont, California: Wadsworth Publishing, 2014.

Hirst, K. Kris. “Laussel Venus – Upper Paleolithic Goddess with a Horn,” http://archaeology.about.com/od/upperpaleolithic/qt/Laussel-Venus.htm

Holy Bible: New International Version. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Zondervan Bible Publishers, 1989.

“Human sacrifice,” Britannica Online Encyclopedia, https://www.britannica.com/topic/human-sacrifice>

Jongko, Paul. “10 Ancient Cultures That Practiced Ritual Human Sacrifice,” 2014, TopTenz, http://www.toptenz.net/10-ancient-cultures-practiced-ritual-human-sacrifice.php

Linsley, Alice C. “Where Did Animal Sacrifice Originate?” Just Genesis (blog), August 2013, http://jandyongenesis.blogsport.com/2011/10/origins-of-animal-sacrfice.html

“Lymphatic filariasis,” World Health Organization (WHO) updated 2016, http://www.who.into/mediacentre/factsheets/fs102/en/

“Lymphatic filariasis,” Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lymphatic_filariasis

Parker-Pearson, Mike. “The Practice of Human Sacrifice.” BBC, 2011. http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/british_prehistory/human_sacrifice_01.shtml

Saint Joseph Daily Missal: The Official Prayers of the Catholic Church for the Celebration of Daily Mass. New York: Catholic Book Publishing Co., 1961.

Shoemaker, Tom. “Images of the Ancient Goddess,” Mesa Community College, 2015, http://www.mesacc.edu/~thoqh49081/summer2015/100web/goddess-images.html

Swezey, Thomas. F. “The World’s Oldest Religious Ritual,” 2002, http://www.winternet.com/~swezeyt/bible/oldestrit.htm

“Venus figures from Russia,” Don’s Maps, http://donsmaps.com/ukrainevenus.html

“Venus figures from the Stone Age arranged alphabetically” Don’s Maps. http://www.donsmaps.com/venus.html

“Venus Figurines, Indonesian Art and the Interconnectedness of the Stone Age,” Biology Magazine, November 2014, http://en.paperblog.com/venus-figurines-indonesian-art-and-the-interconnectness-of-the-Stone-Age-1051077/

“Venus Figurines of the Upper Paleolithic,” Wake Me Up Before You Gogh Gogh blog, December 2013, http://wakemeupbeforeyougoghgogh.blogspot.com/2013/12/venus-figurines-of-upper-paleolithic-art.html

“The Venus Figurines of the European Paleolithic Era,” Ancient Origins, http://www.ancient-origins.net/ancient-places-europe/venus-figurines-european-paleolithic-era-001548

“Venus of Berekhat Ram,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia_org/wiki/venus_of_Berekhat_Ram

“Venus of Gagarino,” Visual Arts Cork, http://www.visual-arts-cork.com/prehistoric/gagarino-venus.htm

“The Venus of Moravany” Venus Figures from the Stone Age, Don’s Maps, http://donsmaps.com/moravanyvenus.html (Don’s Maps is an excellent source.)

“Venus of Willendorf: Exaggerated Beauty,” How Art Made the World, PBS, Episode 1, 2006, http://www.pbs.org/howartmadetheworld/episodes/human/venus/

Whipps, Heather. “Early Europeans Practiced Human Sacrifice,” Live Science, 2007, http://www.livescience.com/1594-early-europeans-practiced-human-sacrifice.html

White, Richard. “Bataille on Lascaux and the Origins of Art.” Creighton University. www.janushead.org/11-2White.pdf

Wynd, Shona, and others. “Understanding the community impact of lymphatic filariasis: a review of the sociocultural literature.” World Health Organization, http://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/85/6/06-031047/en