When I was hiking on Exuma Cay in the Bahamas, I came across a number of flat stones marked with chalk circles. On top, inviting the passer-by to experiment, were two oblong striker stones. The flat stones were musical. The chalk circles marked the best places to hit the stones for clear tones covering most of a scale. This is exactly what ancient people found – unexpected musical stones. Except where I found them entertaining, they found them endowed with magical power.

Ringing Stones

Tanzania has several ringing stones. One is a free-standing stone in Serengeti National Park that’s been struck so many times it has cup-marks in different spots. Its use by the native people is unclear though it might have part of rain-making ceremonies.

Discovering the cup-marks as musical place holders brings something new to the discussion of cup-marks, which are easily the oldest and most common form of rock art in the world.

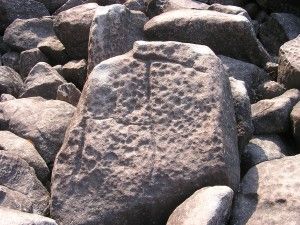

Photo by Wayne Jones

Ringing Rocks County Park, Bucks County, Pennsylvania, USA gives another interesting example. The most famous part of this park is the seven-acre field of boulders that sing. The Lenape Indians considered the area sacred, but it was acquired by the Penn family in 1737. In 1895, Abel Haring, president of the Union National Bank, purchased the land. Apparently he also saw some extraordinary value in the parcel; he refused an offer to sell the land to manufacturer who wanted to quarry the blocks. Haring eventually donated the land to Bucks County. The protected area now includes 128 acres.

Interestingly, the Lenape Indians left marks on the singing stones (See photo, right) much like those in other parts of the world.

Southeastern Pennsylvania and central New Jersey are home to over a dozen ringing rock boulder fields. While some have been obliterated by development, others have been carefully protected and now enjoy a community of supporters and researchers.

Gongs

Single stones have been used as gongs all over the world. Usually, they are suspended and struck to make a single loud sound. Occasionally, multiple gongs are used at once, as shown in the photo from Ethiopia (below).

Lithophones

Lithophones are larger versions of exactly what I found in the Bahamas: a series of stones, either balanced on a frame or suspended from a bar, that produce specific tones when struck. It’s the ancestor of our xylophones and marimbas.

Interestingly, many ancient sounding stone sites also include rock art images. In 1956, archaeologist Bernard Fagg noted that rock gongs in Birnin Kudu, Nigeria also had cave paintings nearby and guessed that the two were linked in some way. M. Catherine Fagg has continued the research at many sites world-wide.

In Azerbaijan, the caves of Gobustan include a rock which emits a deep resonating sound when struck. Rock art images in the cave depict dancers.

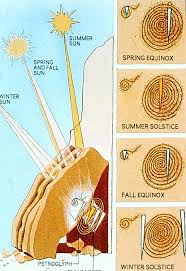

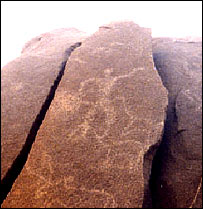

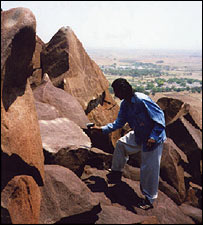

India has many ancient sites that include ringing stones. In Sangana-Kupgal, hundreds of petroglyp hs decorate ringing rocks. When the rocks are struck near the carvings, the stones emit a loud, musical tone. (See photos, left and below)

hs decorate ringing rocks. When the rocks are struck near the carvings, the stones emit a loud, musical tone. (See photos, left and below)

Some of the bigest lithophones come from VietNam, where the instrument still enjoys considerable popularity. In 1949, a French archaeologist named Georges Condominas came across a set of 11 tuned rocks, which he took to be very old, in the central highlands where the M’nong people, originally from Malaysia, lived. Condominas took the stones back to France, and they now live in the Musee de l’homme in Paris.

As it turns out, the area is rich in lithophones, and their popularity has spread throughout the country. You can now listen to quite lively and tuneful performances. My favorite is on YouTube, at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gCHno2kftVU.

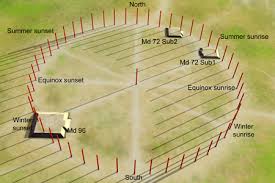

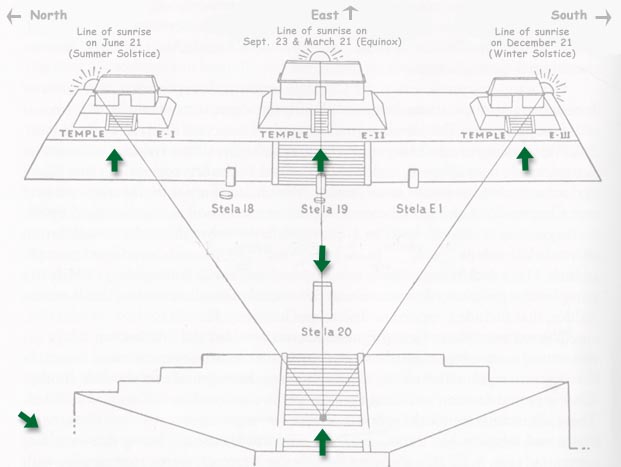

Stonehenge

Photo by Angeles Mosquera

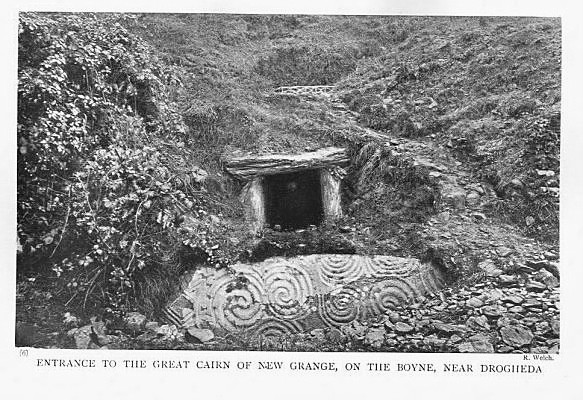

Perhaps the largest and most famous lithophone of all is Stonehenge in Wiltshire, England. According to recent research, about five thousand years ago people moved the giant bluestones, weighing about four tons each, at least 140 miles from a site in Wales to their current home on Salisbury Plain. We have little information about these people, their reason for undertaking this Herculean task, or their plans for the stones once they’d reached the plain. Most research on Stonehenge has concentrated on its astronomical features, including the stones’ alignment with the solstice. However Stonehenge may well have been more than a visual wonder. In recent experiments, British archaeologists found the stones have a distinct ring, not thud, when hit with a hammerstone, and that each stone has a different tone. They described the sounds as something like wooden or metal bells, which brings up the idea of church bells and all of their different functions in an area. Indeed, the Welsh village of Maenclochog (translated as Stone Bells) used Bluestones as church bells up until the 1700’s. Marks on the Stonehenge bluestones indicate they were struck repeatedly, though we do not know the reason.

Dr. Rupert Till, an archaeoacoustics expert, maintained that based on his experiments, Stonehenge would have had extraordinary acoustics that included overlapping echoes. He suggests listeners could have achieved a trance state by listening to music played within the circle.

Stalactites and Stalagmites

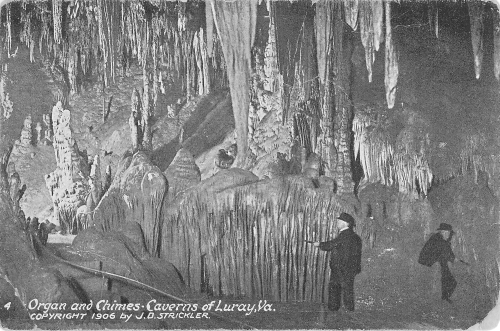

Some cave formations are also emit sounds when struck. Their location within a cave serves to amplify the sound. The Great Stalacpipe Organ in Luray Caverns, Shenandoah National Park, Virginia (USA) is a perfect example. As early as 1878, the musical properties of the stalactites in Luray Caverns were well known. Guides played folk tunes on the stalactites to the delight of visitors. The 1906 postcard from Luray Cavers shows people playing the stalactites with hammers.

The resemblance of a row of 37 tonal stalactites to a pipe organ inspired Leland W. Sprinkle to build the Great Stalactite Organ in 1955, which now uses a keyboard and a series of rubber mallets that strike the stalactites. While this is certainly a commercial venture, it’s a modern reflection of the same awe the ancient people must have felt when they heard the amazing sounds. It’s worth listening to one of many YouTube recordings of the organ being played in the cave. A recording of “Moonlight Sonata” is included in the reading list.

Echoes

Perhaps because ancient people did not understand sound the same way we do, they attributed special powers to the stones themselves. Some singing stones gave voice to the spirits or the ancestors. The most powerful of these were the places where spirits spoke back through echoes. Sound-reflecting surfaces were often viewed as animate beings or as abodes of spirits.

Echo singing

In some cases, magic singing, which is singing with the echoes, was practiced, a skill which indicated a supernatural power. This practice was carried over into medieval churches, where echoes were explained as accompaniment by a choir of angels.

The sound of water and rock

Ancient people often viewed boundary sites as especially powerful.

In Finland, rock art has often been associated with water features. (See photo, above) Antii Lahelma, Finnish rock art expert, has noted in her paper “Hearing and Touching Rock art: Finnish rock paintings and the non-visual” that most of the rock paintings she’s studied were associated with ancient water courses. She claims the rock art images are more than visual, that they celebrate the meeting of worlds, the sound of water on rock. They need to be touched and heard as well as seen.

In Alta Vista, Mexico, Tecoxquin people still visit ancient petroglyph sites as water’s edge to leave offerings. Note the petroglyph on the rock on the left.

We are limited in our understanding of ancient sites by our tendency to put perception in rather clearly limited boxes. It’s art or it’s music or it’s religion. Increasingly, what we’re finding is a world that encompassed all of those things seamlessly.

Sources and interesting reading:

“Ancient Indians made ‘rock music,’ BBC News. 19 March 2004, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/3520384.stm

Amos, Jonathan. “Stonehenge design was ‘inspired by sounds’” BBC News, 5 March 2012, http://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-17073206

Fagg, M. Catherine. Rock Music. Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford, 1997.

“The Great Stalacpipe Organ,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Great_Stalacpipe_Organ

“The Great Stalacpipe Organ: Moonlight Sonata” (video) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HsKUUn29tSs

“Historical,” from Lithophones.com, a comprehensive list of countries with known musical stones. http://www.lithophones.com/index/php?id=2

Keating, Fiona. “Scientists recreate ancient ‘xylophone’ made of prehistoric stones,” IB Times, 15 March 2014, http://www.ibtimes.co.uk/scientists-recreate-ancient-xylophone-made-prehistoric-stones-1440455

“Kupgal petroglyphs,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kupgal_petroglyphs

“La Pietra Sonante,” Pietro Pirelli, musician (video). Powerful ringing sound! http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p5Q5bW3bYMM

Lahelma, Antii. “Hearing and Touching Rock Art: Finnish rock paintings and the non-visual,” Academia. http://www.academia.edu/2371980/hearing_and_touching_rock_art_ Finnish_rock_paintings_and_the_non-visual/ A very interesting paper.

LeRoux, Mariette and Laurent Banguet, “Cavemen’s ‘rock’ music makes a comeback,” The Telegraph, 17 March 2014, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/music/10702186/Cavemens-rock-music-makes-a-comeback.html

“Litofonos.” Piedras que hablan…con musica. (video) www.youtube.com/watch?v+qY1L–irW70

“Musical Stone, Namibia,” http://www.namibian.org/travel/archaeology/musical-stone.html

“A Mystifying Experience: The Alta Vista Petroglyphs,” A Gypsy’s Love blog, agypsyslove.com/2001/07 – photo of Alta Vista glyphs

“Ringing Rocks,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ringing_rocks

“Ringing Rocks: A Geological and Musical Marvel,” It’s Not that Far: Great places to see and things to do near Eastern Pennsylvania, 10 September 2010, http://www.itsnothtatfar.com/2010/09/ringing-rocks/

“Rock gong,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rock_gong

Schultz, Colin. “Stonehenge’s Stones Can Sing,” Smithsonian.com. 10 March 2014. http://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news-stonehenges-stones-can-sing-180950034/?no-ist

“A short introduction to musical stone,” from Lithophones.com. http://www.lithophones.com/index/php?id=45

“The Sky at Night,” BBC 2-minute video about drums at a model of Stonehenge, 5 July 2013, http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p01ccpsp

“Swakop River, Namibia (video – a little windy but interesting) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hrlPxT4MS8.

Tellinger, Michael. “Stone Xylophone.” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6aG-e7zGq3Y

Tellinger, Michael. “Stones that ring like bells.” http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uX2P8utjk3A

Waller, Steven J. “Archaeoacoustics: A Key Role of Echoes at Utah Rock Art Sites,” Utah Rock Art, Volume 24

Waller, Steven J. “Rock Art Acoustics” – a very extensive collection of information about sites and research. https://sites.google.com/site/rockartacoustics/