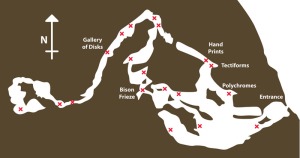

After visiting eleven decorated caves in northern Spain, including two replicas, I came away with a tremendous sense of admiration and respect for the artists who worked on them. My favorite, by far, was El Castillo, the largest of four caves on the beautiful mountain of the same name (pictured below). For starters, it has yielded evidence of an incredibly long span of occupation – over 150,000 years.

That means it was home to Neanderthals, who, most texts explain, first appeared in Europe about 300,000 years ago. Homo sapiens (modern humans) started living in the El Castillo cave about 40,000 years ago. Both groups apparently shared the area for about 5,000 years. All those dates are subject to challenge.

El Castillo (modern entrance shown in photo) is no dank, narrow cave. Back in the Paleolithic era, it had a natural arch opening and a wide area lit by sunlight, making it a bright, airy spot for a campsite, a meeting area, or even a village shelter in bad weather. It also has a fine view of the valley below. ( See photo.)

In the front section now under excavation, different levels seem clearly separated. The ones with human occupation look much darker because they include carbon from fires. The periods in which the cave was occupied only by animals are marked by pale yellow bands. But how do researchers know that a certain level was Neanderthal rather than modern human? It turns out it’s based on agreed-upon dates and tool styles. Neanderthals succeeded Homo Heidelbergensis in Europe about 300,000 years ago and died out between 35,000 and 40,000 years ago for reasons unknown. If the carbon dates for a layer come back between 40 and 300 thousand years old, it’s identified as Neanderthal. Maybe. Certain stone tools and objects made from antler and bone are also typical of this period. The truth is the dates keep changing, and the whole field of study is in a state of flux.

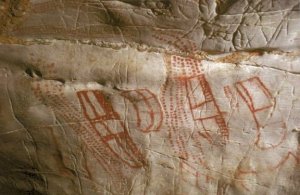

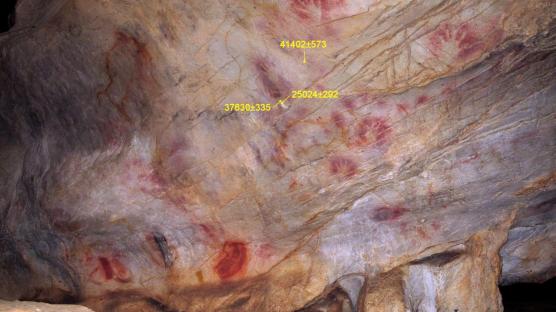

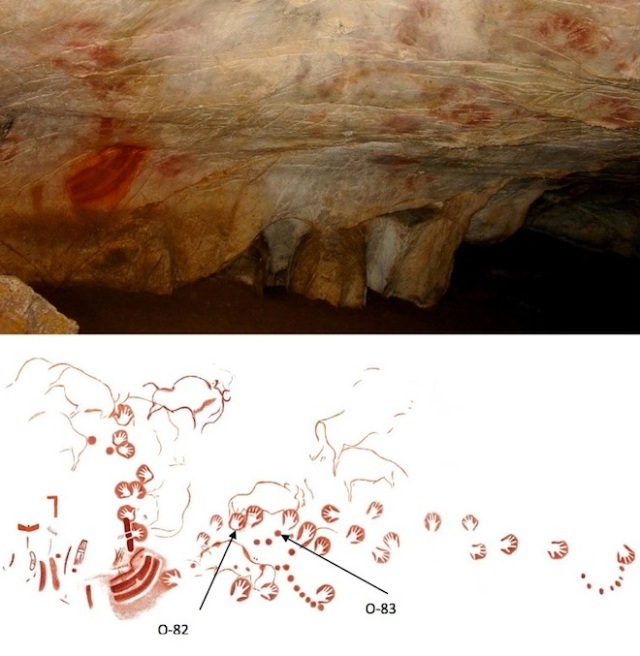

So, did Neanderthals paint at least some of these dots on the walls of El Castillo, a couple of which, including one of the dots in the photo, have been dated to over 41,000 years old? Another part of the same panel was found to be 25,000 years old, and yet another to be 37,000 years old. (See labelled photo. The number of years is listed first, then the margin of error.) That covers 16,000 years on a single panel of the cave! If Neanderthals did paint some of that panel, it would be toward the end of their reign in Europe and the beginning of the ascendancy of modern humans. According to a study published in Nature, pockets of Neanderthals survived in Europe until 39,260 years ago. Even given that, it’s not clear which group painted the dots on the wall of El Castillo.

One problem we face in answering that question is the paucity of dated samples. It’s very expensive to complete carbon dating or uranium-thorium dating on a piece of cave art, and the process right now requires taking a tiny sample of the paint off the wall. Once dating techniques improve and the cost comes down, we’ll know a lot more about the dates and sequence in which different paintings were made.

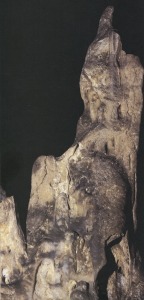

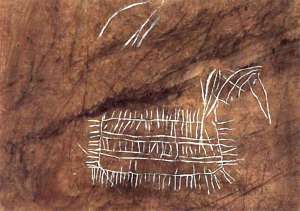

Right now, archaeologists are reluctant to say more than it’s possible that some of the art in El Castillo might have been made by Neanderthals. They admit that Neanderthals may have painted a couple of seals on a stalactite in a cave near Malaga, Spain (photo), and they may have carved bird bones and deer teeth, and left crosshatch marks on a cave wall in Gibraltar. But their underlying belief is that only modern humans had the sophistication to create art or think symbolically. That assumption, though, is being challenged.

Three Interesting Sites

The Lozoya Child in Central Spain

In a cave north of Madrid, in what’s come to be called The Valley of the Neanderthals, researchers identified the ritual burial of a Neanderthal toddler they called the Lozoya Child. Placed on fire sites nearby were horns and antlers from bison, aurochs (cattle), and red deer. These are also animals commonly painted on Paleolithic cave walls in northern Spain. The fires were dated between 38,000 and 42,000 years old. Enrique Baquedano, director of the Regional Archaeological Museum of Madrid, thinks the cave might have been used by Neanderthals as a place to mourn and remember the dead

The Stalagmite Circle in France

It’s also interesting to consider a 1990 find in Bruniquel Cave in southwestern France. Alerted by 15-year-old Bruno Kowalsczewsi and his father, local cavers squeezed through a narrow opening into an open chamber containing animal bones. Some 1100′ (336 meters) farther back in the cave, they found several stalagmites that had been purposely broken, then many more. About 400 pieces had been laid in two rings. Others had been propped up against them or stacked in piles, some marked with red or black lines (Photo from the National Geographic article listed with sources). There was also a mass of burned bones. These were not natural formations. Scientist and caver Sophie Verheyden took over the exploration of the cave after the original archaeologist died, and called on archaeologist Jacques Jaubert and stalagmite expert Dominique Genty for their help. They tested the stalagmites in 2013 by drilling into them and pulling out test cores. In studying the cores, they realized part was old minerals and part was new minerals that had been laid down after the fragments were broken off. The date of the divide was clear but shocking: 176,500 years ago. There were no known modern humans in the area at the time. It had to be the work of Neanderthals. Verheyden’s team’s study appeared in the journal Nature in 2016.

Also interesting was the depth of the placement in the cave, which would have had no natural light, so the makers had to work by torches or fires. The structure leads to the idea of ritual behavior in the cave. “A plausible explanation is that this was a meeting place for some type of ritual social behavior,” noted Paola Villa from the University of Colorado Museum. More than 120 fragments have red and black streaks not found anywhere else in the cave. (Curiously, many of the decorated caves I saw included black marks on stalactites.) “Some type of ritual behavior” is a pretty wide umbrella term, but the idea of honoring the dead, especially a child, has real resonance in the caves I visited in northern Spain, as do the red circles and black marks.

Verheyden is continuing her exploration of the cave, hoping to answer some of the many questions about the people who used it with such a clear purpose.

The Shanidar Skeletons of Iraq

Skeletons of eight Neanderthal adults and two infants, dated from 65,000 years ago to 35,000 years ago were found in Shanidar cave in northern Iraq. One of the adult males was given a pile of stones including worked points made of chert. And there was evidence of a large fire by the burial site. (The possible scene pictured comes from the Smithsonian article listed with sources.) Pollen grains found on the adult male skeleton known as Shanidar 4 led some to say he had been buried with flowers known for their medicinal properties: yarrow, cornflower, bachelor’s button, ragwort, grape hyacinth, horsetail, and hollyhock. Later, skeptics claimed the pollen might have been brought in by gerbils or bees. I’m not sure why bees would bring pollen to a body in a cave, but that’s the complaint. Some of the skeletons showed evidence of wounds that had been tended and healed.

The Red Lady

A modern human woman, dubbed “The Red Lady,” was buried about 19,000 years ago in a cave called El Miron, across the valley from El Castillo, and covered with red ochre and flowers. No one has suggested these pollen grains were the work of gerbils or bees.

All this is to say that the Neanderthal influence in El Castillo and other caves should not be dismissed or minimalized. It’s seems clear that Neanderthals used caves for more than shelter from the storm long before modern humans arrived on the scene.

The Creative Juncture

Even if modern humans living in El Castillo didn’t meet their Neanderthal predecessors, they would have noticed their work on the cave walls. Perhaps the combination of cultures was enough to spur an artistic explosion. Imagine the conversation: “Look, they put dots along this wall, and hand prints. This place has important energy relating to death and life. Let’s add something of our own to claim this space.” Originally, I thought of it as a competition, just as a gang tags a wall in a disputed territory and another gang comes along and covers the marks with theirs. A talented artist puts up a beautiful tag. The opposite one is even better. Competition spurs growth and invention. But, in the case of the El Castillo artists, they seem to have incorporated many of the same symbols as their predecessors, which suggests a continuity of thought rather than a total replacement of one ideology with another.

An Even Greater Shock

Everything we think about the Neanderthals and modern humans is based on the timeline. But what if that timeline is not quite the whole story? A new possibility was suggested in a study described in Nature Communications. After analyzing the DNA from a 100,000 year old Neanderthal skeleton discovered in Bruniquel Cave in southwestern Germany, researchers found the mitochondrial DNA resembled that of early modern humans. In an attempt to explain how this could be, scientists suggested that about 220,000 years ago, a female member of the line that gave rise to Homo sapiens mated with a male Neanderthal. Imagine the scene at the family dinner.

If this theory is proven to be true, it would make our family tree a good deal more complicated!

So it’s not hard to see the progression that played out in El Castillo and the explosion of creative energy that accompanied the co-existence of these two groups.

It will be interesting to see what we learn about our cousins in the next ten years or so.

Sources and interesting reading:

“Bruniquel Cave,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bruniquel_Cave

Calaway, Ewen. “Europe’s first humans: what scientists do and don’t know,” Nature, 22 June 2015, http://www.nature.com/news/europe-s-first-humans-what-scientists-do-and-don-t-know-1.17815/

Clottes, Jean. Cave Art. London: Phaidon Publishing, 2010.

“Divje Babe Flute” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Divje_Babe_Flute/

“Early Human Migrations,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Early_human-migrations

Edwards, Owen. “The Skeletons of Shanidar Cave,” Smithsonian magazine, March 2010. http://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/the-skeletons-of-shanidar-cave-7028477/

Garrido Pimentel, Daniel, and Marcos Garcia Diez. Discover Prehistoric Cave Art in Cantabria: The Caves of Chufin, El Castillo, Las Mondedas, Hornos de la Pena, El Pendo, Covalanas, and Cullalvera, published by Sociedad Regional de Educacion, Cultura y Deporte, Gobierno de Cantabria, no date given.

Ghose, Tia. “Ancient Mourners May Have Left Flowers on ‘Red Lady Grave’” Live Science, 20 May 2015, https://www.livescience.com/50897-red-lady-grave-flowers.html

Gibbons, Ann. “Neanderthals and modern humans started mating early,” Science magazine, 4 July 2017, http:/www.sciencemag.org/news/2017/07/Neanderthals-and-modern-humans-started-mating-early?utm_campaign=news_daily_2017-07-04/

Gray, Richard. “Cave fires and rhino skull used in Neanderthal burial rituals,” This Week, New Scientist, 28 September 2016, https://www.newscientist.com/article/mg23230934-800-cave-fires-and-rhino-skull-used-in-neanderthal-burial-rituals/

Jaubert, Jacques, Sophie Verheyden, Dominique Genty, and others. “Early Neanderthal constructions deep in Bruniquel Cave in southwestern France,” Nature (534) 02 June 2016, https://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v534/n7605/full/nature18291.html/

“Neanderthals, humans may have coexisted for thousands of years,” Associated Press, 22 August 2014, CBC, http://www.cbc.ca/news/technology/neanderthals-humans-may-have-coexisted-for-thousands-of-years-1.2742067/

Rincon, Paul. “Neanderthal ‘artwork’ found in Gibraltar cave,” BBC News, 1 September 2014, http://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-28967746/

“Shanidar Cave,” Wikipedia, https?en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shanidar_Cave

Than, Ker. “Neanderthal Burials Confirmed as Ancient Ritual,” National Geographic, 16 Deccember 2013, http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2013/12/131216-la-chapelle-neaderthal-burials-graves/

Than, Ker. “World’s Oldest Cave Art Found – Made by Neanderthals?” National Geographic News, 14 June 2012, http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2012/06/120614-neanderthal-cave-paintings-spain-science-pike/

UNESCO World Heritage Center. “Cave of Altamira and Paleolithic Cave Art of Northern Spain,” UNESCO, http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/310

Von Petzinger, Genevieve. The First Signs. New York: Atria Books, 2016.

Wong, Sam. “Neanderthal artist revealed in a finely carved raven bone,” New Scientist Daily News, 29 March 2017, https://www.newscientist.com/article/2126292-neanderthal-artist-revealed-in-a-finely-carved-raven-bone/

Yong, Ed. “A Shocking Find in a Neanderthal Cave in France,” The Atlantic, May 2016. https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2016/05/the-astonishing-age-of-a-neanderthal-cave-construction-site/484070/

difficult to master. Archaeologist Paul Pettitt reported that using the two tubes to spray the slurry left them light-headed. Many heard a persistent whirring or whistling noise in their ears. It’s not hard to see how this would have added to the impression of entering a different world.

difficult to master. Archaeologist Paul Pettitt reported that using the two tubes to spray the slurry left them light-headed. Many heard a persistent whirring or whistling noise in their ears. It’s not hard to see how this would have added to the impression of entering a different world.