El Castillo Cave

El Castillo Cave in northern Spain is famous for containing the oldest cave art in Europe: a red disk that was painted on the cave wall at least 40,800 years ago, perhaps as long as 42,000 years ago. These dates caused a major uproar because it’s just about the time modern humans (Homo sapiens sapiens) are thought to have arrived in Western Europe. Before then, Neanderthals (Homo neanderthalensis) occupied the area. So debate rages about whether the red dot was the work of our Neanderthal cousins, modern humans, or perhaps a hybrid of the two. The latter is certainly a possibility; we now know the two races/species interbred. Or perhaps the meeting of the two lines of hominins released a flood of new creativity on both sides.

You can find a good introductory video, “Paleolithic Cave Arts in Northern Spain,” on YouTube. It also shows how close the quarters are inside some sections of the cave.

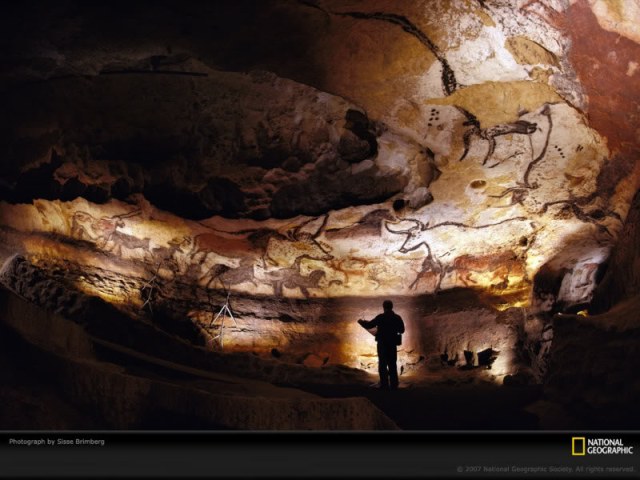

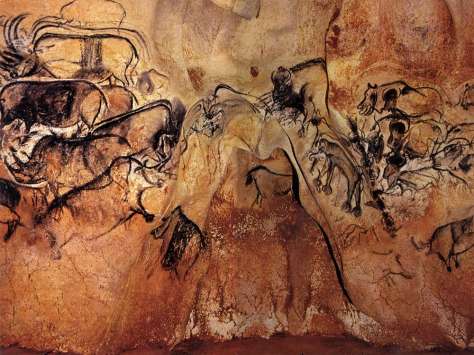

The cave also contains many very old hand stencils, the oldest of which are at least 37,000 years old. Just for reference, the oldest paintings in Chauvet Cave in France are 32,000 years old, and the famous Lascaux Cave paintings are about 20,000 years old.

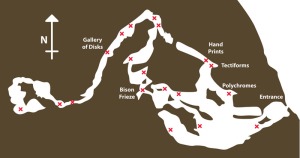

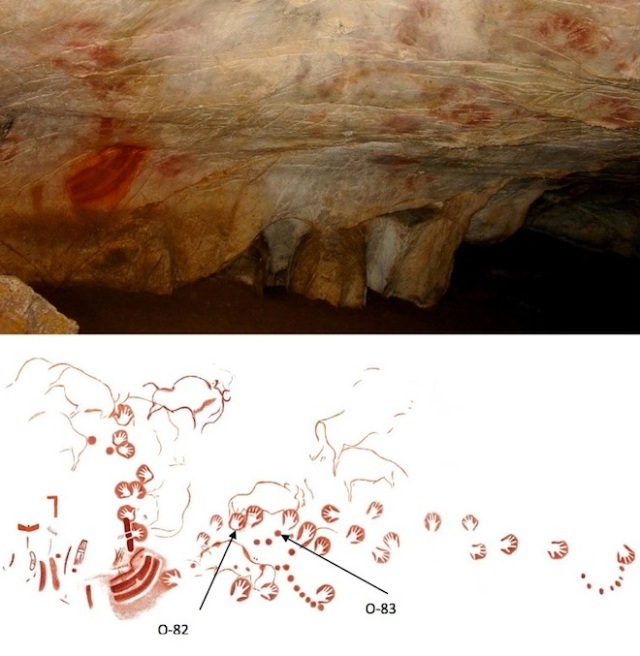

People are drawn to contests determining the first and the oldest, so most of the attention given to El Castillo has been directed at the very old dots and hand stencils. Two of those tested are marked on the photo.

But El Castillo’s value is more than just its antiquity.

The 13,000 year span

Experts once considered the drawings made on the walls of El Castillo the product of a single time period – about 17,000 years ago. This somewhat arbitrary date was assigned because they thought France had the oldest cave art, so any cave in Spain had to be younger than Lascaux Cave in France. When scientists were able to date the art by dating the calcite deposits that had formed over the top of it, they were amazed at its age. And its range.

The oldest, the red disks, are over 40,000 years old. Some may be 42,000 years old. But some disks are far younger, at 20,000 years old.

The disk and hand print that were analyzed by Pettitt, Pyke, and Zilhao are marked with numbers on the sketch below.

Some of the hand stencils, mostly near the front and middle sections of the cave, were apparently painted more than 37,000 years ago, but some of the more recent hand stencils are 24,000 years old.

The animal figures painted over the hand stencils are generally more recent than the stencils, in some cases by thousands of years.

So the artwork in the cave was created over thirteen thousand years. Thus, it’s impossible for us to make a single assumption or interpretation about all the paintings in the cave. The space, though probably considered very powerful and important, may have served very different purposes over those years. What’s interesting is the ancient artists’ decision to continue to mark the cave, often using the same imagery, and in some cases to mark right over the top of earlier signs.

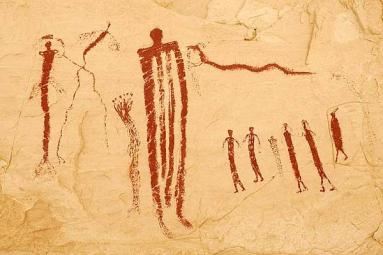

The Panel of the Hands

One of the most intriguing sections of the cave is the Panel of Hands, located far back in one leg of the cave.

The stenciled hands included in it were created by placing a hand over the rock and blowing a mixture of red ocher and water over it. The slurry was held either in the artist’s mouth and blown out directly over the hand, or in a clam shell. (Several shells, mixing stones, and hollow bird bones were found on site.) When researchers attempted to recreate the process of creating a hand stencil, they tried two methods: they blew out a mixture held in their mouth for some and for others they used two tubes, one inserted in the slurry and one held in the mouth. The passage of air from the mouth tube over the slurry tube creates a vacuum that then allows the slurry to be sprayed over the hand. Those of you old enough to remember artists’ fixative blowers before aerosols will be familiar with the process. As the Dick Blick art supplies site explains, “Place the short tube in your mouth and the long tube in the bottle of fixative. Blow gently and evenly, aiming at your drawing. This atomizer can also be used to spray watercolors and thinned acrylics for special effects.” (In the photo below, a modern artist uses an atomizer for special effects.)

When experimental archaeologists attempted to replicate the hand stencil technique with two hollow bird bones forming the atomizer, they found it  difficult to master. Archaeologist Paul Pettitt reported that using the two tubes to spray the slurry left them light-headed. Many heard a persistent whirring or whistling noise in their ears. It’s not hard to see how this would have added to the impression of entering a different world.

difficult to master. Archaeologist Paul Pettitt reported that using the two tubes to spray the slurry left them light-headed. Many heard a persistent whirring or whistling noise in their ears. It’s not hard to see how this would have added to the impression of entering a different world.

Who left those hand prints?

Another interesting discovery colors our view of this panel. Older interpretation was that the hand prints were those of men seeking success in the hunt, but research now shows that three-quarters of the hand prints and stencils in the caves of France and Spain were made by women. Dean Snow, who analyzed hundreds of hand stencils in eight caves in France and Spain, showed that the hand prints carry a distinct signature. Women tend to have ring and index fingers of the same length. Men’s ring fingers tend to be longer than their index fingers. Snow’s data showed that 24 of the 32 hands in El Castillo were female. Their reasons for making the prints remain a mystery.

The semi-circle of dots

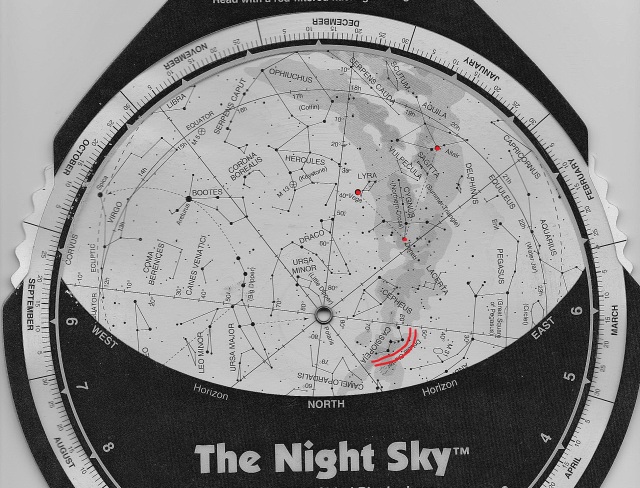

Another curious feature of this panel is the semi-circle of dots on the far right. Several scholars have interpreted this as a representation of the Northern Crown constellation (Corona Borealis). It’s a fascinating theory. (I admit this whole section is sheer speculation but fun!)

In northern Spain, the Northern Crown constellation is visible in the night sky from spring to fall. Since El Castillo seems to have been occupied only during those seasons, it would make sense to include it as a sort of seasonal marker. If that’s true, it shows an impressive level of sophistication in our relatives so long ago.

If you want to push that theory, you could point to the position of the Northern Crown on the far right and see the vertical line of hands as the standing Milky Way, as the sky would have appeared in the spring. The line of hands across the middle would cross the center of the sky in early May.

The dark curved bands would appear at the base of the Milky Way, just about where Cassiopeia would be.

Addendum, January 2016

There’s something about the El Castillo Frieze of Hands that I can’t let go. I thought initially that the Northern Crown constellation was notable enough to include in the post, though of course it is speculation. However, I now think that the entire panel, perhaps excluding the bison drawings, relates directly to the summertime night sky.

The section marked with the heavy red lines that resemble a boat looks like the summer position of the constellation Cassiopeia. It appears, about 9:00 PM, as an uneven “W” in the summer and an uneven “M” in winter, while it appears to stand on one leg during spring and fall.

Above it rises the Milky Way, with the three stars of the Summer Triangle marked near the top, the most conspicuous asterism in the summer sky, made up of the brightest stars from the constellations Aquila, Lyra, and Cygnus.

With Cassiopeia in the position marked, this would be a mid-summer star scene, typical of about 9:00 PM in July.

In the drawing shown earlier, the somewhat enigmatic figure in the center of the panel could refer to a number of constellations or combinations of them. If it is Perseus to the Pleiades, that angle would be typical of a later summer sky, late August or September.

Finally, the only times the Northern Crown would look the way it’s painted on the far right of the panel (arms pointing up) would be in spring or fall (March and October). The constellation appears in the spring and disappears from the night sky in the fall.

The three constellations would then reference three different times during the summer.

It’s fascinating to consider the possibility that our ancestors so long ago not only understood the patterns in the stars and their relationship to the seasons but could reproduce them deep inside a cave.

Forgive me if I’ve stepped into the land of speculation. This one wouldn’t stay quiet.

Addendum to the Addendum, June, 2017

After visiting El Castillo and looking at the panel in question, I have to admit I was wrong. It’s not a clear semi-circle of stars but more like a full circle. I suppose that’s the danger of working from a diagram rather than the real thing.

None of this detracts from the cave itself, which is incredibly powerful and impressive.

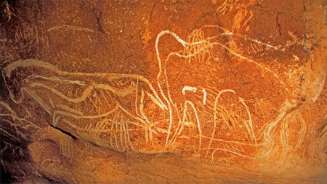

The Bison

Interestingly, at least eight yellow bison figures were painted over the top of the stenciled hands in the Frieze of Hands. More appear in other sections of the cave, often painted in black. The bison images are remarkably similar – showing the same rump and single hind leg, large hump and (often partial) head with two horns, as if they all followed the same template. They appear at the top of the vertical line of hand stencils in the photo on the left, and over the left and central portions of the horizontal line of hands. In the image below, lines of yellow ocher descend from the bison’s mouth, as if it’s bleeding.

While experts once thought the hand stencils on this panel were a way for hunters to spiritually connect to the bison, perhaps to ensure success in the hunt, current research shows the people who used the cave didn’t eat bison. Mostly they depended on deer for meat. As the famed anthropologist Claude Levi-Strauss pointed out, “Animals were chosen [for representation] not because they were ‘good to eat’ but because they were ‘good to think.’”

Besides, the bison were painted later than the hands – in some cases, much later. The hands aren’t touching the bison. The bison are crowding out the hands, or superseding them.

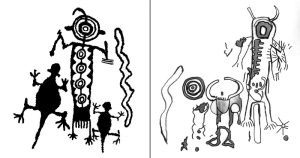

Bison also appear prominently in both Chauvet (France) and Altamira (Spain), as well as Las Monedas, Buxu, and El Pendo. Rather than a form of hunting magic, the bison image, which seems very similar from one site to another, might have represented a spirit power, in particular a male power in a female cave. The figure on the left is from El Castillo. The one on the right is from Buxu Cave (Spain).

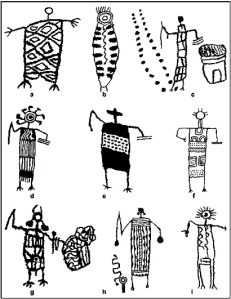

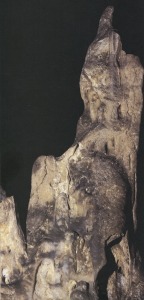

The Bison Man

This bison spirit idea is supported in El Castillo by the “Bison Man” figure. Deep in the recesses of the cave is a carved stalactite figure known as the Bison Man. It seems to show the figure of a bison standing upright or climbing a cliff. There’s a nice YouTube video of the Bison Man at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FdbMAZgC7VA showing not only the carving of the bison but also the shadow effect when a light is shined on the whole formation, transforming it into a bison-human moving through the cave. The photo (left) does not show the figure very well. Start with the hind leg, toward the bottom of the photo. Then follow the standing figure, which looks as more like a wolf hybrid than a bison to me. The body uses the natural form of the rock and emphasizes it with black drawing.

The Bison Man figure is reminiscent of the Sorcerer figure in the back of Chauvet Cave (France), which combines both male and female characteristics, and the Sorcerer figure in Trois Freres Cave (France) which combines features of reindeer, bison, bear, horse, and human male. It would be interesting to find out the date for Bison Man and compare that to the dates of the bison drawings. If indeed the bison is the mark of a particular cult or group, it would seem logical for those people to put their symbol over the top of earlier ones, just as the horse and mammoth figures were superimposed on earlier animal forms in Chauvet. Or the way Roman Catholic Spaniards in Peru built their churches on top of Inca stonework.

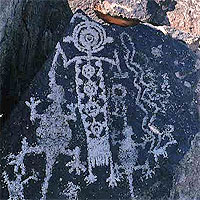

The Techtiforms

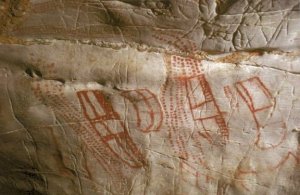

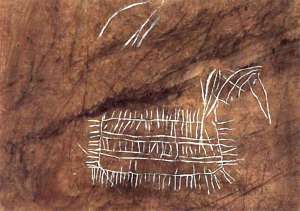

There’s much to learn from the drawings made so long ago in El Castillo cave, including the meaning of the bizarre abstract figures, called techtiforms, that appear at the base of the vertical line of hands and other places in the cave, each time accented very definitely. (Photo, right.)

These forms are usually explained away as drawings of boats, maps, buildings, corrals, or simply the product of hallucinations or shamanic trance. But they obviously had a very specific meaning and great importance. That’s why they were repeated and emphasized. Perhaps findings in other caves in the area will help us understand. The drawing from Buxu Cave shown in the photo (below left) seems to suggest an animal form, maybe a horse, but it’s hard to tell. I suspect that as we make more discoveries, we’ll get a better idea of what these diagrams mean.

Studying these very old drawings reminds us that our ancestors were far more sophisticated than we guessed.

If it turns out that at least some of the El Castillo artists were Neanderthals, the evidence of their art should help revise the negative image of them we’ve held for so long.

Sources and Interesting Reading:

“Alphecca, jewel in Northern Crown,” Wikipedia, http://earthsky.org/brightest-stars/alphecca-norathern-crowns-brightest-star/

Borenstein, Seth. “Spanish cave paintings shown as oldest in the world,” USA Today, 14 June 2012, http://usatoday30.usatoday.com/tech/scienc/story/2012-06-14/cave-paintings-spain/55602532/1\

“Buxu Cave,” Don’s Maps, http://donsmaps.com/buxu.html

“Claude Levi-Strauss,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Claude_1_%C3%A0vi-Strauss/

“Corona Borealis,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Corona_Borealis/

“El Castillo Cave,” Don’s Maps (an excellent source), http://www.donsmaps.com/castillo.html

“First Painters May Have Been Neanderthal, Not Human,” Wired, 14 June 2012, http://www.wired.com/2012/06/neanderthal-cave-paintings/

“Fixative atomizer,” Dick Blick Art Supplies catalog

Garcia-Diez, Marcos. “Ancient paintings of hands,” BBC Travel photos of El Castillo

Garcia-Diez, Marcos, Daniel Garrido, Dirk L. Hoffmann, Paul B. Pettitt, Alistar W. G. Pike, and Joao Zilhao, “The chronology of hand stencils in European Palaeolithic rock art: implication of new U-series results from El Castillo Cave (Cantabria, Spain), Journal of Anthropological Sciences, Vol 93 (2015) 135-152.

Hughes, Virginia. “Were the First Artists Mostly Women?” National Geographic News, 09 October 2013, http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2013/10/131008-women-handprints-oldest-neolithic-cave-art/

“A journey deep inside Spain’s temple of cave art,” BBC Travel, www.bbc.com/trael/story/20141027-a-journey-deep-inside-spains-temple-of-cave-art

“New Research uncovers Europe’s Oldest Cave Paintings,” The New Observer, 24 September 2013

“The Night Sky,” the original 2-sided planisphere (star guide), copyright 1992, David Chandler

“Paleolithic Cave Arts in Northern Spain: El Castillo Cave, Cantabria,” a video available on YouTube, with English subtitles, https://www.youtube.com

Rappenglueck, Michael. “Ice Age People find their ways by the stars: A rock picture in the Cueva de el Castillo (Spain) may represent the circumpolar constellation of the Northern Crown,” Artepreistorica.com, http://www.artepreistorica.com/2000/12/ice-age-people-find=their-way-by-the-stars

Rimell, Bruce. “El Castillo – Formative Image from the Upper Palaeolithic,” Archaic Visions, http://www.visionaryartexhibition.com/archaic-visions/el-castillo-formative-images-from-the-upper-palaeolithic/

Sanders, Nancy K. Prehistoric Art in Europe. Yale University Press, 1995.

Subbaraman, Nidhi. “Prehistoric cave prints show most early artists were women,” NBC News 15 October 2013, http://www.nbcnews.com/science/prehistoric-cave-prints-show-most-early-artists-were-women-8C11391268

Zim, Herbert, and Robert H. Baker. Stars: A guide to the constellations, sun, moon, planets, and other features of the heavens. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1956. Still a cute book.

mber also contains a striking panel of red dots made by coating a hand with red ochre and pressing it against the wall. To the right of the red dots is a section with red dots and lines that seem to pour out from a central fissure in the rock. The cruciform symbol appears several times on the panel (photo, left).

mber also contains a striking panel of red dots made by coating a hand with red ochre and pressing it against the wall. To the right of the red dots is a section with red dots and lines that seem to pour out from a central fissure in the rock. The cruciform symbol appears several times on the panel (photo, left).

most enigmatic part of the End Chamber, and indeed the whole cave, is the V-shaped rock formation mentioned above. It’s painted with the head of a male bison and the pubic triangle and leg of a woman that seems to fade into a lioness painted on the flat section (See photo, left). It’s often called the Sorcerer. Though its function is unknown, it certainly encourages comparisons with the androgynous Spirit Master of western US cave art. Yahwera, as the spirit master is known, keeps all the animals inside the earth and then releases them through a crack or crevice. People mark the location of the portal to the Spirit Master’s cave with hand prints and drawings on the rock.

most enigmatic part of the End Chamber, and indeed the whole cave, is the V-shaped rock formation mentioned above. It’s painted with the head of a male bison and the pubic triangle and leg of a woman that seems to fade into a lioness painted on the flat section (See photo, left). It’s often called the Sorcerer. Though its function is unknown, it certainly encourages comparisons with the androgynous Spirit Master of western US cave art. Yahwera, as the spirit master is known, keeps all the animals inside the earth and then releases them through a crack or crevice. People mark the location of the portal to the Spirit Master’s cave with hand prints and drawings on the rock.