Wow – What is it?

Bizarre, vaguely human figures in rock art have long puzzled viewers. They look a little like people yet clearly they’re something else. Why do they have weird heads, often without facial features? Why do they often have fewer than five fingers on each hand (or occasionally more)? Why do they have long torsos and missing limbs?

Learning to see through others’ eyes

In the 19th century, anthropologist Edward B. Tyler introduced the concept of animism to describe the widespread ancient belief that all entities, including humans, animals, and natural features such as mountains, rivers, and trees, have souls, or spirits. All of these entities are interconnected, sharing a magical power. The person is identified not just by a physical body but by all of the connections made to the rest of the spirit world. Tyler found this belief to be the oldest and most common spiritual belief in the world. (It’s also the basis of “The Force” in the Star Wars films.)

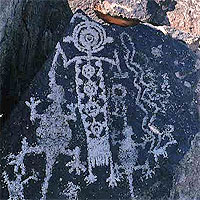

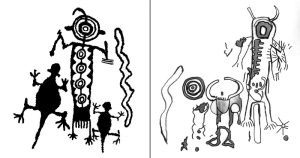

In the 1980s, David Lewis-Williams argued that many odd figures in rock art, including the spirals, dots, and therianthropes (figures that combine human and animal characteristics) were images typical of a visionary trance brought on by chanting, drumming, fasting, and taking hallucinogenic drugs. He pointed out that many of these images are typical of visual distortions associated with trance experiences. They have been replicated many times in experiments involving LSD. Lewis-Williams argued that the rock art figures like the one in the photo (left) represented the shaman in the process of transformation into something supra-human, able to change physical form and slip between worlds.

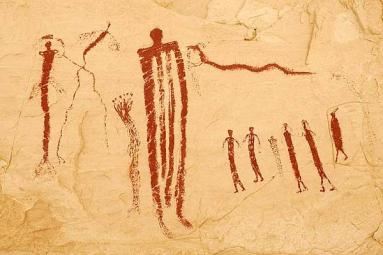

He described the famous fresco on the wall of the Game Pass Shelter in the Drakensberg region of South Africa as a shaman in a dream state connecting with the dream beast, the eland. The shaman is bleeding from the nose, as is the eland; their legs are crossed in exactly the same position. The eland is dying in order to bring rain to the people. The shaman has entered a pseudo-death in order to make the connection with the dream beast. For Lewis-Williams, the therianthrope – the figure combining human and animal characteristics – represents the shaman in his or her transformed state. (Photo left, drawing below)

He described the famous fresco on the wall of the Game Pass Shelter in the Drakensberg region of South Africa as a shaman in a dream state connecting with the dream beast, the eland. The shaman is bleeding from the nose, as is the eland; their legs are crossed in exactly the same position. The eland is dying in order to bring rain to the people. The shaman has entered a pseudo-death in order to make the connection with the dream beast. For Lewis-Williams, the therianthrope – the figure combining human and animal characteristics – represents the shaman in his or her transformed state. (Photo left, drawing below)

In 1976, Patricia Vinnicombe published the results of her work with the Drakensberg (South Africa) rock art paintings, in a book titled People of the Eland. In it, she reviewed stories told by San (Bushmen/Khoi San) people and recorded since the 19th century. Some told of a shaman catching a “rain beast” – usually a female ox, eland, elephant or other large herbivore. This was done through a trance, with the help of the group chanting, drumming, and dancing. Then the beast was sacrificed, and rain would fall where the beast was killed.

Interestingly, two San men that Patricia Vinnicombe interviewed saw the therianthropes in this image as mythical people of an earlier race, the First Bushmen, not images of transformed shamans.

These seem to be two very different explanations, but they may in fact be complementary. The shaman in a trance state may be the means of contacting spirit entities, including animal spirits, nature spirits, and spirits of the dead.

South central California rock art

New research on rock art in southeast California may suggest a slightly different way of seeing the famous panel in South Africa – and perhaps another mysterious figure found in the deepest part of Chauvet Cave in southern France.

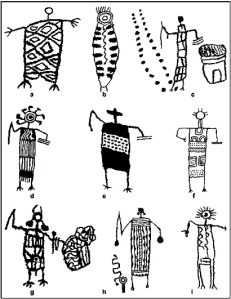

The Patterned Body Anthromorphs

While studying thousands of rock art images in what is now the China Lake Air Force Base, Dr. Alan Garfinkle and his associates noted over 700 strange figures they called Patterned Body Anthromorphs, images notable for a long torso marked with various patterns, a head devoid of normal facial features, and truncated or missing legs, often with three toes. Sometimes a twisted snake accompanied the figure. In many cases, there was no gender evident, but in others, the figure had male, female, or both male and female characteristics. Almost all carried a staff or atlatl (dart thrower). Some carried a bag of seeds, which trailed out in lines behind the figure.

The Kawaiisu and other American Indian groups that lived in the area where the paintings appeared shared similar beliefs, which Dr. Garfinkel felt could provide a frame of reference for the rock art figures. Caves were seen as important places, imbued with sacred power. A spirit named Yahwera lived in a cave where the spirits of all the animals resided, even animals that had been killed.

In the spring, Yahwera opened the portal and allowed the regenerated animals to fill the land. Yahwera also provided healing medicines (“magic songs”) and successful hunts. Occasionally, a human, through accidental discovery or shamanistic transformation, could enter the world of Yahwera through a portal in a rock surface or a cave. There, below ground, the visitor would see all the animals, including those waiting to be reborn. Guarded by a large snake, the androgynous Yahwera was the keeper of the animals, wisdom, and power.

Images of Yahwera were inscribed on the sites of the portals. A known portal to the home of Yahwera was located near a spring and marked with an image of the Animal Master: a humanoid figure with red circles for the face, a feathered headdress and clawed feet. Next to the figure was a snake almost as tall as the main figure.

The two drawings included (left) are representations of the patterned body anthromorphs in the Coso rock art collection (on the left) and the known representation of Yahwera, the guardian of the animal spirits (on the right).

The Yokuts, another tribe in the area, refer to rock art sites as “shaman’s caches,” vaults of magic power. When a shaman spoke to the rock, the portal opened, and the Spirit Master gave the shaman magic songs and wisdom.

The shaman as intermediary

The shaman talks to the rock, but the Spirit Master opens it. In this sense, the shaman is the intermediary. Because he can break the confines of this world, he is able to intercede for the people, asking the Spirit Master to release the game the people need to live. (I’m referring to the shaman as male though San people indicate that any male or female could accept the dangerous role of dream healer if desired.) The shaman delivers the request, not only for game but also for rain, wisdom, or cures for sickness. In this way, the shaman is acting in the same role as a modern priest, delivering the faithful’s requests to their Spirit Master.

One Kawaiisu narrative tells of a man who took jimsonweed (or raw tobacco in other versions) and found Yahwera’s cave. Inside he saw many animals, including deer and bear, who spoke the same language as the people. Yahwera explained that the animals weren’t really dead; they were only waiting to be reborn. At the end of the experience, the man was cured of his illness and left the cave through water at the end of a tunnel. When he came out, he found himself far from his starting point. He’d been gone so long, his people thought he had died.

In the Coso rock art, the strange figures on the rock surface are probably not shamans in a transformative state. According to tribal beliefs recorded in the 19th and 20th century, the figures represented the Spirit Master, the keeper of the animals, the source of magical power. The shaman was the one who is sensitive enough to find the portal to the Spirit Master’s realm and powerful enough to traverse the dangerous realms beyond this one.

Rock art images like the one included here from Utah seem to indicate a hierarchy of spirits because one figure is so much larger and dominates the image. While all things living and dead may share in spirit energy, some are apparently far more powerful than others.

An interesting side note:

The Memegwashio Indians of Quebec explain the red handprints on the rock over a sacred place as the mark of the spirits where they close the portal.

And another:

Cheyenne traditional beliefs held that the realm of deep earth could be accessed through sacred caves. In certain caverns animal spirits gathered, from which the animals might be released in physical form or refused rebirth.

And now to ancient cave art in Europe

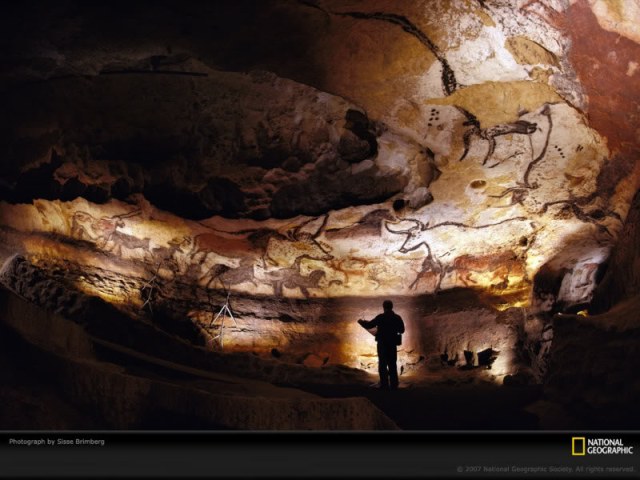

Please forgive the jump from North American cave art to Europe 35,000 years ago. I don’t pretend to know the cultural references that would explain the beautiful ancient cave art of southern France and northern Spain, but others more knowledgeable than I have seen some commonality that bears examination. And the similarities are hard to ignore.

The oldest cave painting in Europe, possibly the work of our Neanderthal cousins, is a series of handprints on the wall of El Castillo Cave in Spain dated to 40,800 years ago. The cave shows no evidence of use as a living space, so it was apparently visited for other purposes. If the artists were Neanderthals, they were painting at the end of their reign. Not many years later, modern humans took over. Still, the idea that they may have marked the cave as special and that modern humans continued the association is intriguing. We now know that Neanderthals and modern humans interbred. Perhaps their ideology was passed along as well.

As Enrico Comba points out in his paper, “Amerindian Cosmologies and European Prehistoric Cave Art: Reasons for and Usefulness of a Comparison,” rock art of Paleolithic Europe is an art of caves, mostly in remote areas hard to access. The figures are mostly animals. The few human figures are hybrids – human/animal crosses. The cave functions as a womb and a refuge for the animals, much the way that Yahwera’s cave held the animals in the California rock art references.

The second-oldest known cave art in Europe is in Chauvet Cave, at least 32,000 years old. The animals painted are realistic yet dreamlike, incomplete, presented in moving groups without any ground line.

In the back of the cave, in the last and deepest chamber, is a curious image known by some as “Venus and the Sorcerer.” It is a combination of a bull head and a pubic triangle surrounded by female legs that blend into the front leg of the bull and the leg of a lioness.

It’s not much of a stretch to see this image as the Spirit Master, the keeper of the animal spirits in the cave, similar to the androgynous spirit that the shaman called upon in California art to release the animals held in the cave so they could be reborn in the spring.

Once again, the cave would function as the home of the animals, many of them pregnant with new life. It’s certainly an interesting possibility – that the mysterious Sorcerer/Venus figure in the very back of Chauvet Cave serves the same function as the Spirit Master.

Sources and interesting reading:

“Ancient Rock Art of the World,” Rock Art Documentary, DVD, ILecture Films, Boilerplate Productions, made in conjunction with the Bradshaw Foundation

“Art of the Chauvet Cave,” Ice Age Paleolithic Cave Painting, Bradshaw Foundation www.bradshawfoundation.com/chauvet

“Cave of Forgotten Dreams,” DVD, Chauvet Cave documentary film by Werner Herzog, IFC Films, 2010

“Cave Painting,” Wikipedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cave_painting

“Cave Paintings (40,000 – 10,000 BC)” Artchive.com http://www.artchive.com/artchive/C/cave.html

Comba, Erico, “Amerindian Cosmologies and European Prehistoric Cave Art: Reason for and Usefulness of a Comparison,” Arts journal, 27 December 2013 www.mdpi.com/journal/arts

Garfinkel, Alan, with Donald Austin, David Earle, and Harold Williams, “Myth, ritual and rock art: Coso decorated animal-humans and the Animal Master,” Petroglyphs.US, 19 May 2009 <http://www.petroglyphs.us/article_myth_ritual_and_rock_art.htm>

Garfinkel, Alan and Steven J. Waller, “Sounds and Symbolism from the Netherworld: Acoustic Archaeology and the Animal Master’s Portal,” Pacific Coast Archaeological Society Quarterly Vol.46, 4

Howley, Andrew. “70th Anniversary of the Discovery of Lascaux” National Geographic Newswatch, 17 September 2010, http://newswatch.nationalgeographic.com/2010/09/17

Lymer, Kenneth, “Shimmering Visions: Shamanistic Rock Art Images from the Republic of Kazakhstan,” Expedition (Journal of the Museum of Pennsylvania), vol. 46, no. 1

Solomon, Anne. The Essential Guide to San Rock Art. South Africa: ABC Press, 1998

“The Sorcerer (cave art)” Wikipedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Sorcerer_(cave_art)

“Talking Stone: Rock Art of the Cosos,” DVD starring Dr. Alan Garfinkel, distributed by the Bradshaw Foundation

Than, Ker. “World’s Oldest Cave Art Found – Made by Neanderthals?” National Geographic News, 14 June 2012, http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2012/06/120614

“Venus and the Sorcerer” image from http://www.bradshawfoundation.com/chauvet

Witze, Alexandra, “Rock Art Revelations?” American Archaeology, Summer 2014, vol 18, no. 2, 33-37.