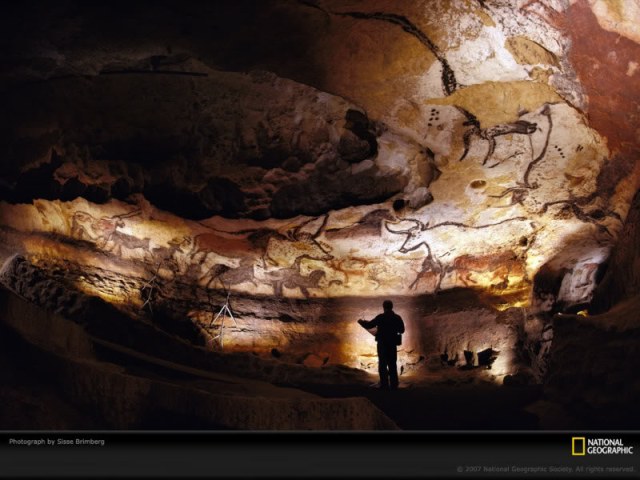

In 1994, three cave explorers were surveying a cave in the Ardeche region of southern France when they discovered another cave nearby. That cave, now world-famous, carries the name of the lead explorer: Jean-Marie Chauvet. More than 400 meters long, it features several “rooms” or sections covered in amazing paintings, some of which have been found to be between 30,000 and 33,000 years old. The famous paintings in France’s Lascaux Cave, in comparison, are about 20,000 years old. The Chauvet dates were so old that many archaeologists refused to believe them even after artifacts had been tested repeatedly. That’s because Chauvet art challenged a long held theory that art “progressed” or developed greater sophistication as modern humans developed. Thus early art should be primitive, minimal, and naïve. Instead, Chauvet art showed great power and inventive design effects.

Chauvet Cave Layout

Chauvet Cave is a 400-meter (1312’) long network of galleries and rooms divided by very narrow sections. A landslide 26,000 years ago completely sealed off the cave, preserving its contents until its discovery in 1994. So when we study the images of the cave provided by Jean Clottes, Werner Herzog, and the French Ministry of Culture we see exactly what the ancients – and some wild animals – left behind.

Several rockslides closed the original opening. When Jean-Marie Chauvet, Christian Hillaire, and Eliette Brunel found the current opening, they had to squeeze through a very narrow space that led to a deep shaft. Eliette Brunel, the only woman in the group, went first, climbing down to the large chamber that now bears her name. When she saw drawings on the wall, she cried out, “They have been here!” Indeed they had, though the artists and the viewers had missed each other by an almost unimaginable stretch of time.

Brunel Chamber

In the Brunel Chamber, an ancient artist must have felt the mineral flows on one wall looked like a mastodon, for the form has been outlined in red ochre. The mastodon is one of the central animal forms in the cave decorations.

This cha mber also contains a striking panel of red dots made by coating a hand with red ochre and pressing it against the wall. To the right of the red dots is a section with red dots and lines that seem to pour out from a central fissure in the rock. The cruciform symbol appears several times on the panel (photo, left).

mber also contains a striking panel of red dots made by coating a hand with red ochre and pressing it against the wall. To the right of the red dots is a section with red dots and lines that seem to pour out from a central fissure in the rock. The cruciform symbol appears several times on the panel (photo, left).

Farther along in the Brunel chamber is a panel of three bears drawn in red ochre (photo, right). Almost every drawing in the front half of the cave is done in red. Drawings in the back of the cave are done in black.

Like most of the figures in the cave, these feature a clear head, shoulder and top line while legs are merely suggested.

Also in the Brunel Chamber is an animal form made of dots – handprints actually, all from the same artist. Together they make up another mammoth.

The Red Panels Gallery

The eastern wall of this gallery holds several panels of hand prints, dots, and red figures of a bear/hyena and a panther (photo, left). Note the similarity in drawing style to the bears pictured above, especially in the treatment of the face and the added smudging or stumping around the eye ridge and nostril.

The Cactus Gallery

The most prominent features in this section are a red mammoth painted on a hanging u-shaped formation (photo, right) and a red bear on the wall (photo, left).

Note the similarity of the style of the bear drawing with the previous bear and hyena drawings.

Past the Cactus Gallery, the cave abruptly narrows, the floor drops and the ceiling drops, making a tight passageway that forms a natural boundary between the two sections of the cave. The art is also divided by this point. The front section is almost exclusively painted in red figures and forms. From footprints left behind, researchers know that men, women, and children visited the front section. The back chambers, including the monumental panels painted in black, are very different and may have had far fewer visitors.

The Back of the Cave

The Hillaire Chamber

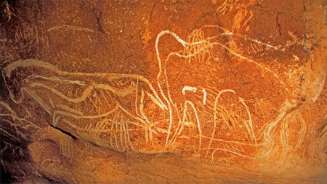

The Hillaire Chamber has a deep depression in the center, about ten meters (32’) in diameter and four meters (13’) deep. The walls around it feature over a hundred paintings as well as engravings of a horse and a mammoth, (shown in photo, left) and an owl. Some other engravings to the left of the horse have been scratched out.

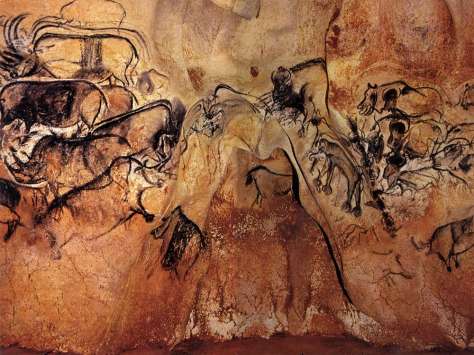

The most famous panel in this chamber is the one featuring a collection of horses, rhinos and aurochs (photo), as well as fainter marks that might have been earlier figures. According to researchers who have recreated the order of painting, the horse heads are the most recent addition to the panel. Next to the group is a fissure in the rock, so the horses seem to be emerging from it.

On the left wall is a panel of horses as well as a pair of cave lions. The horse heads in this panel seem to be drawn by the same artist as those on the other panel, or at least in the same style. The lion heads show especially delicate shading work and stippling around the muzzle.

Researchers have recreated the sequence of strokes involved in painting the lions. See photo below.

Also in this chamber is a panel of drawings of aurochs, bison, horses, and others – all done in brief outlines with none of the shading or power of the previously mentioned panels.

The Skull Chamber

This section gets its name from a cave bear skull left on a prominent rock. Over 3700 cave bear bones were found in Chauvet Cave, thought to belong to at least 190 different individuals. (The next most common was wolf bones, belonging to six individuals.)

The End Chamber

Beyond the Megaloceros passage is the End Chamber, which contains some of the most astounding art panels in the cave. A young mammoth was drawn over older figures of rhinos. Three lions, using the same shading and stippling pattern as the earlier ones, were drawn over earlier figures. Multiple rhinos appear on one side of a crevice while what looks like a pack of lions chases bison and other animals on the other side of the crevice. A single horse appears in a scraped-clean recessed area (photo below left). The photo on the right shows the whole section, complete with the phallic protrusion described below and the hole on the cave wall.

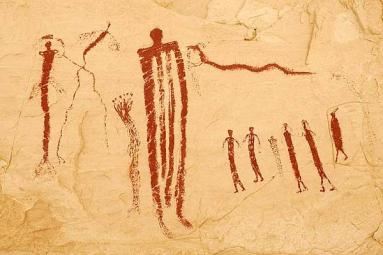

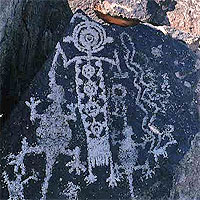

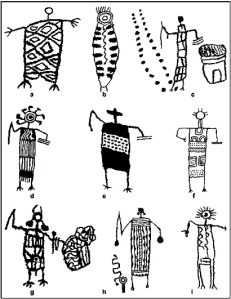

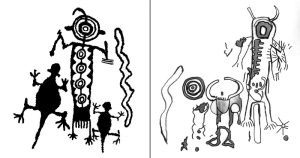

The most enigmatic part of the End Chamber, and indeed the whole cave, is the V-shaped rock formation mentioned above. It’s painted with the head of a male bison and the pubic triangle and leg of a woman that seems to fade into a lioness painted on the flat section (See photo, left). It’s often called the Sorcerer. Though its function is unknown, it certainly encourages comparisons with the androgynous Spirit Master of western US cave art. Yahwera, as the spirit master is known, keeps all the animals inside the earth and then releases them through a crack or crevice. People mark the location of the portal to the Spirit Master’s cave with hand prints and drawings on the rock.

most enigmatic part of the End Chamber, and indeed the whole cave, is the V-shaped rock formation mentioned above. It’s painted with the head of a male bison and the pubic triangle and leg of a woman that seems to fade into a lioness painted on the flat section (See photo, left). It’s often called the Sorcerer. Though its function is unknown, it certainly encourages comparisons with the androgynous Spirit Master of western US cave art. Yahwera, as the spirit master is known, keeps all the animals inside the earth and then releases them through a crack or crevice. People mark the location of the portal to the Spirit Master’s cave with hand prints and drawings on the rock.

Past the End Chamber is a small area known as the Sacristy, which contains only the figure of a mammoth drawn in black with tusks emphasized by engraving.

What do these images mean?

Doodling

There’s always some expert who claims ancient people were incapable of abstract thought; therefore anything they produced must be simply doodling, without any specific meaning. It’s hard to believe these people actually looked at the images in the photographs.

Hunting Magic

Some experts claim the cave paintings were a form of hunting magic. Hunters drew images on the walls to increase their luck in the hunt. The problem is that most of the animals on Chauvet’s walls weren’t animals the people hunted. And, unlike the images in Lascaux Cave, these animals do not appear with arrows piercing them. Often they appear to be emerging from cracks in the cave wall, or in the case of the End Chamber, from the depth of the cave itself, like a womb of life presided over by the androgynous figure of the Sorcerer.

The Brilliant Crazy Ones

David Whitley, in his book Cave Paintings and the Human Spirit: The Origin of Creativity and Belief, argues that amazing ancient cave art is the work of one or more individuals we would call mentally ill. Specifically, he suggests bi-polar disorder and schizophrenia. These mood disorders, he says, provide the springboard for creativity. He backs up his argument with studies of shamans who endured mental illness and through their struggles were able to experience the mythic creation of the world. He claims that in the case of Chauvet, the enlightened crazy ones “used art to permanently materialize their spirit contact. They created something in the real world [art] to illustrate what was in fact unreal.”

While I don’t rule out enlightened crazy artists, I think the process of art creation in Chauvet was more gradual that that thesis implies. The art in Chauvet was an on-going process. The first stage covered two thousand years! Newer artists painted over older work. Sometimes they purposely scratched out older images. Older images tend to be simpler line figures without varying intensity of line or shading while the most recent work is very sophisticated indeed. But then, the later artists had a great gallery of previous work to study.

Neanderthals?

Studies of the earliest cave art at El Castillo Cave in Spain, dated to over 40,000 years old, revealed the strong possibility that the first artists to leave their marks on the cave walls were Neanderthals. They left red dots and series of lines as well as two figures clearly resembling fish. Perhaps the impetus for the great art of Chauvet and later Lascaux in southern France came from the folks who lived in the area for thousands of years before Homo sapiens sapiens.

Trance

Other experts, following the lead of David Lewis Williams, show that a trance state, brought on by fasting, drugs, repetitive sound, light deprivation, or even the toxic air inside the cave could have resulted in the impression that the mineral deposits on the walls were indeed animals coming out of the rock. This idea is backed up by the outlined mammoth shape in the front half of the cave. Trance was and is critical to religious practices in many parts of the world. Through trance, shamans – people especially in tune with the spirit world through their constitution and their training – can bridge the gap between the world of spirits and the world of people in order to restore balance between them.

In many parts of the world caves are still seen as portals to the Underworld, powerful places that form a passage between worlds.

These theories may in fact overlap. Perhaps inspired by the claw marks bears left on the walls, early residents left their own marks. Later, visionary individuals may have understood the cave as a place to contact the spirit world. These people and those who believed them would want to touch the walls that formed the only barrier between them and the otherworld. They would want to put their mark on the cave, to become part of it. Later, the cave might become so powerful in local society it had to be claimed for a specific group and covered with their symbols. As that power shifted, so did the symbols.

Competition

Even among the most recent works in Chauvet, there seems to be some competition involved, perhaps by individual artists, clans, villages, or other groups. In the Skull Chamber, older red hatch marks were covered with an ibex drawing which was later scratched out and a reindeer added. The mammoth outline is often drawn over older rhinos. A mammoth has been included in various parts of the cave (including the front and far back) over earlier images. Lions are often drawn over older figures (including on the feline panel in the End Chamber), but the most common over-draw is the horse head, occurring often as a head scratched right over the top of other figures or as the suggestion of a whole body, such as the figure in the Niche of the Horse in the End Chamber, which was drawn over a scraped area. Other older red figures were effaced, along with a series of dots.

Several of the charcoal drawings seem to have been made by the same master artist who didn’t hesitate to cover or replace earlier works. In the photo, it’s clear that the artist has scraped the left panel clean to make a stronger contrast between the white background and the black charcoal.

The mammoth artist seems to have a different style entirely but also “tagged” many different areas in the cave. This artist tends to use only an outline, sometimes of the head, shoulders, and front leg, and sometimes the whole body. The very last image in the cave is just such a figure. (See photo, right) The young mammoth was drawn first in charcoal, then the tusks were emphasized by engraving.

Competition among artists may have also driven rapid developments of style. The fully shaded horse heads and lion figures make a far more powerful statement than the smaller outlines of earlier efforts.

Conclusions

It may be difficult to explain how the ancient people perceived these cave drawings, but one conclusion is easy: The paintings in Chauvet Cave should show how absurd the whole Social Darwinism/March of Progress theory really is. Obviously, the development of humankind is not a slow and steady march toward greater ability and sophistication, with modern humans at the top of the mountain. Our distant ancestors had art, culture, and abstract thought 30,000 years ago!

While the cave is closed to the public to protect its contents, you can visit a replica that is now open near the cave. Or check out the French Cultural Ministry’s map of Chauvet Cave at http://www.culture.gouv.fr/fr/arcnat/chauvet/en/ It provides an overview of the cave shape as well as an interactive display of the paintings, human artifacts, and animal remains in each section. It’s worth seeing!

Sources and Interesting Reading:

Balter, Michael, “Did Neandertals Paint Early Cave Art?” Science/AAAS/News, 14 June 2012, http://news.sciencemag.org/2012/06/did-neadertals-paint-early-cave-art

“Chauvet,” French Ministry of Culture site, http://www.culture.gouv.fr/fr/arcnat/chauvet/

“Chauvet Cave (ca.30,000 BC)” Hellbrunn Timeline of Art History, Metropolitan Museum of Art, http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/chav/hd_chav.htm

“Chauvet Cave,” Don’s Maps, www.donsmaps.com/chauvetcave.html – This is an excellent source for photos of the paintings and maps of the galleries!

“Chauvet Cave Paintings: Prehistoric Murals, Ardeche, France: Discovery, Significance, Cave Layout,” Visual Arts Cork, http://www.visual-arts-cork.com/prehistoric/chauvet-cave-paintings.htm

Clottes, Jean. Chauvet Cave: The Art of Earliest Times. University of Utah Press, 2003

Clottes, Jean. Cave Art. Phaidon Press, 2010. This coffee table book has fabulous full-color photos of very famous and some less famous European cave paintings and engravings.

“Decorated Cave of Pont d’Arc, known as Grotte Chauvet-Pont d’Arc, Ardeche,” United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), World Heritage List, http:whc.unesco.org/en/list/1426

Herzog, Werner. Cave of Forgotten Dreams (film) 2011, IFC Films

Hitchcock, Don, “Floor Plan of Chauvet Cave,” from Philippe et Fosse (2003) with additional text from Chauvet Cave: The Art of Earliest Times, by Jean Clottes (2003)

“Introduction to the Chauvet Cave,” Bradshaw Foundation, http://www.bradshawfoundation.com/chauvet/chauvet_cave_paintings.php

“Prehistoric Colour Palette: Paint Pigments Used by Stone Age Artists in Cave Paintings and Pictographs” Visual Arts Cork, http://www.visual-arts-cork.com/artist-paints/prehistoric-colour-palette.htm

Than, Ker. “World’s Oldest Cave Art Found – Made by Neanderthals?” National Geographic, 14 June 2012, http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2012/06/120614-neanderthal-cave-paintings…

Thurman, Judith “First Impressions: What does the world’s oldest art say about us?” The New Yorker 23 June 2008, http://www.newyorker/com/magazine/2008/06/23/first-impressions

Whitley, David. Cave Paintings and the Human Spirit: The Origin of Creativity and Belief. Amherst, New York: Prometheus Books, 2009.

Photos: Photos from the French Ministry of Culture’s website are credited to Dominique Baffier and Valerie Ferugio. Other photos come from Don’s Maps Chauvet post, at www.donsmaps.com/chauvetcave.html Some of the photos on his post come from Jean Clottes and his team, some from National Geographic photographers.